ST. GEORGE — After arriving by motorcycle escort at the St. George Lions Veterans of Foreign Wars Building, family and friends surprised Navajo code talker Samuel Tom Holiday with a party for his 90th birthday on Saturday morning. The Marine Corps League, Utah Dixie detachment #1270, lined the paved entryway to the front door and performed a gun salute.

This was the first time Holiday had ever been honored to this extent.

“For me the recognition for code talkers so far is not enough,” said Holiday’s daughter Helena Begaii. “In history books they only give the code talkers like two pages. The United States used 23 different tribes.”

(report continues below)

Videocast by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

From 1943-1945 Holiday served in combat with the Fourth Marine Division during World War II. Throughout this time he served duties on the island of Roi Namur, Kwajalien, Tinian, Saipan and Iwo Jima. Military historians note that during the first 48 hours of the invasions at Iwo Jima more than 800 coded messages were sent and received by Navajo radio units with 100 percent accuracy. The Navajo language was not recorded and almost impossible to learn. It served as a code the Japanese failed to crack; a language that Holiday was told as a child not to speak because Navajo had nothing to offer.

In an excerpt from his autobiography “Under the Eagle,” published in 2013, Holiday describes a memory from boarding school:

“There was also to be no more Navajo religion and traditional ceremonies. ‘Learning English will help you in your future’, she said. ‘the Navajo way will not help you; it has nothing so you must speak English.'”

Upon being discharged, Holiday was told not to unveil his duties as a code talker, but as he got older he wanted a full historical recount to be told. He collaborated with historian Robert S. McPherson and it took five years to finish and is the only book that recounts the entire life of a code talker not just the war.

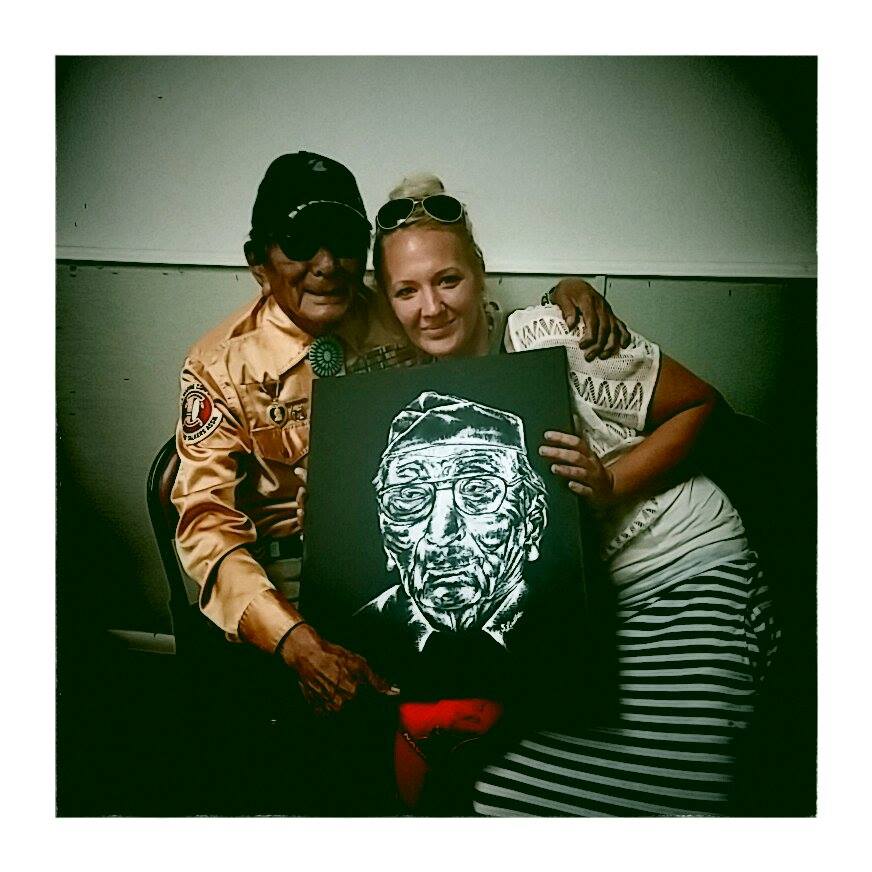

Dressed in his code talker uniform — a red hat depicting the United States Marine Corps, turquoise jewelry representing the Navajo sacred stone, a gold shirt symbolizing corn pollen, with a patch on the arm denoting the Fourth Marine division, light-colored pants signifying mother earth and shoes the color of abalone which is also a sacred stone — Holiday shared his childhood and experiences as a code talker.

He grew up near Monument Valley by a mountain known as Eagle Rock. His family, members of the Todich’inii or the Bitter Water Clan, herded sheep and lived according to Navajo traditions. When Holiday was 4 years old he remembers being told about his great-grandmother being taken as a prisoner during the “long walk.”

“They rounded up all the Navajo — old ones, little ones — herded them up like sheep kept them for four years as prisoners, a lot them were Navajo,” Holiday said. “That’s the reason I was really scared of white people, I didn’t even know what they looked like.”

Holiday’s mother Betsy Yellow played a significant role in his early education. She taught him about herbal medicine, nature’s remedies and survival properties of desert plants.

“We didn’t know about white man’s medicine,” he said. “If you get thirsty out in the desert there are plants that hold water that you can suck the juice from. This is survival. All these teachings really came in handy during the war.”

It wasn’t until he was 12 years old that he encountered a white person; after an extended stay at the hospital for a knee injury, he was enrolled in boarding school.

Holiday enlisted to join the Marines when he was 18, just before he completed coursework for a vocation school in Provo. On the date of Pearl Harbor, he was at school playing basketball, somebody came to the door and yelled ‘the Japanese are attacking America,’ he said.

During basic training in California, the Marines would participate in 25-mile marches where they were only allowed to carry one canteen of water per person. After two or three days several of the marines would have to be picked up by a truck. This was a time that the Navajos showed their adeptness to survival because of a shared understanding of nature.

“There were plants we knew we could get juice from. All the Navajos made it to the end of the march,” Holiday said. “And you wonder why the Marines would say ‘those damn super Indians’?”

During the war, Holiday — whose grandfather was a medicine man — wore a traditional Navajo pouch around his neck, with four sacred stones and yellow corn pollen wrapped in a leather binding believed to provide protection and to calm fears. Many Navajo Marines wore these pouches or carried eagle feathers on their person.

During the years overseas, Holiday was mistaken twice for a Japanese soldier and suffered hearing loss in his left ear after walking past an exploding mortar shell on shore.

“I started yelling: ‘no I’m not going back. I came here to fight a war not to stay in Sick Bay,'” he said. “I couldn’t hear, there was noise all around, shots going off, and I couldn’t hear.”

After enlisting 39 code talkers, recruiters realized the significance of the Navajo language as a code. They promised Holiday that after serving he would receive an added bonus, that his mother would be taken care of, that she would get running water, but it didn’t happen. Instead he received around $300, orders to not talk about the code and returned to the still existing segregated America.

“After I was discharged I came back to Flagstaff (Arizona) and was trying to get a room at a hotel and they told me ‘it’s full, it’s all full’,” he said. “The next day, I went back to the main town, I said: ‘let’s go eat.’ They said: ‘no no no you can’t eat this food.’ That happened to me twice. It didn’t feel right. I fought next to black man, white man, Mexican and came back to segregation.”

After returning from the Marines, Holiday became a Navajo police officer and married Lupita Mae Isaac in 1954. Together they have eight children, 33 grandchildren, 23 great-grandchildren and one great-great-grandson.

“He never made a big deal about himself as a code talker,” Begaii said. “He didn’t see himself that way. My dad feels like this is his land, his people’s land, with the four sacred mountains and the importance of taking care of it. He was fighting for his country. The best thanks are anonymous. Sometimes we are in a restaurant and we are waiting for our ticket and then we find out someone paid for it.”

Holiday’s grandson, Roderick Redhouse, sung and played a hand drum powwow circuit birthday song. Afterward, the color guard offered Holiday an honorable membership for detachment #1270.

“I never saw my dad as a Navajo code talker,” Begaii said. “He was always just daddy.”

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

The Marine Corps, Dixie Utah color guard stand at the Lion's Veterans of Foreign Wars Building, to honor Navajo code talker Samuel T. Holiday for his 90th birthday, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

The Marine Corps, Dixie Utah color guard honor Navajo code talker Samuel T. Holiday for his 90th birthday, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

Members of Samuel Holiday's family enjoy the celebration, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

A photo of Navajo code talker Samuel Tom Holiday sits atop a table, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

At Samuel Holiday's celebration, tables were set up to display pictures and military awards that were given to Holiday, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

The Marine Corps, Dixie Utah color guard at Lion's Veterans of Foreign Wars Building, honors Navajo code talker Samuel T. Holiday for his 90th birthday, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

Honoring Navajo code talker Samuel T. Holiday for his 90th birthday, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

Navajo code talker Samuel T. Holiday celebrates 90, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

Navajo code talker Samuel T. Holiday, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo by Samantha Tommer, St. George News

The Marine Corps, Dixie Utah color guard stand at the Lion's Veterans of Foreign Wars Building, to honor Navajo code talker Samuel T. Holiday for his 90th birthday, St. George, Utah, May 31, 2014 | Photo courtesy of Preston Holiday, St. George News

Related posts

- Native Americans’ Memorial powwow: ‘We fought as brothers;’ STGnews Photo Gallery

- Together for Taleah; princess run supports 5-year-old fighting cancer

- Washington County Veterans Court, now in session

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2014, all rights reserved.

You are a great example of a true american. God bless.

Beautiful story of an extraordinary gentleman. Thank you, sir, for your service. I am grateful for your part in my freedom. God bless you and your wonderful family.

Grateful to what he did for us. Im Navajo and happy that I speak my language. http://www.gomyson.com come visit my site. I think of Code Talkers when I code on the computers.

D.o.b. 1940. Thank you for helping me, by God’s grace, keeping me alive, all these years. The American Indians (all tribes), are owed more than a debt of gratitude that America can never pay; I do pray you will be given much more recognition. You were here FIRST, yet you are not CELEBRATED. May you always be in God’s heart, as well as mine, as I do remember World War II.