SANTA CLARA — It was a Friday night in 1940 when the Gestapo, reading from a piece of paper, announced that Faigla Fischel was to be turned over to them. And it was on that Friday night that Faigla was loaded onto a cattle car bound for Neusalz, a forced-labor camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. She was 11 years old and she would never see her parents again.

For Faigla Fischel Moncznik, now 88 years old, memories of her experience during the Holocaust are still fresh.

For her daughter, Santa Clara resident Penny Lindenbaum, memories of growing up in Israel and in the Bronx, New York, as a child of two survivors in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust are equally real, even painful.

Lindenbaum remembers many discussions at social gatherings relating to the camps. She heard the words Auschwitz, Dachau and others, she said, and the names of people her parents said never made it out.

As a young girl, Lindenbaum said, she wasn’t sure who never made it out or exactly what they never made it out from.

Then, as she grew older, Lindenbaum said, she realized others had extended family at many of the social gatherings her family attended but she herself had no aunts, uncles, grandparents or cousins. So she asked her mother why they had no other family.

The short reply was always the same: “Because they are all dead.”

Lindenbaum’s family settled in the United States and slowly the details of her parents’ lives came out – the concentration camps, the suffering, entire families being wiped out – all of it.

The story that follows is an an account of what happened to Faigla – Faigla Fischel who survived the Holocaust and married another survivor, Berl Moncznik.

Speaking with St. George News by telephone from her home in New Jersey, Faigla Fischel Moncznik vividly recalled that Friday night she was taken from her family.

They were living in an apartment in the Ghetto at Bedrin, Poland, where they had lived since being removed from their own home nearby a few years earlier.

The Gestapo was standing in the apartment doorway, she said, reading her name off of a list.

As she was led away from the apartment, her mother began crying and begged the officer not to take her.

“She was crying and said, ‘but she’s just a baby,'” Lindenbaum said of Faigla’s mother.

Faigla was first taken to a schoolyard near the Ghetto. She remembers a guard telling her not to cry, telling her she would see her parents again soon.

She would have no way of knowing then that her parents would die in one of the concentration camps, as would all of her large extended family – every one of them, she said, except two of her siblings and one aunt.

Within days Faigla was sent to the Neusalz forced labor camp. There she worked alongside other young girls her age in a factory, where older female prisoners in the camp looked after her. She spent four years at Neusalz until she and others were forced on a death march.

In January 1945 more than 1,000 Jewish women were marched from Neusalz to Flossenburg. Flossenburg was a concentration camp 200 miles away in southeast Germany. Of the 1,000 women that departed Neusalz, only 200 reached the camp alive after more than a month of marching. The 800 who never made it were either beaten or shot to death.

Death marches were the forced marches of prisoners over long distances under unbearable conditions. They were abused by their accompanying guards and often killed during the marches. The Nazis conducted many such death marches during the Holocaust, mostly near the war’s end following the evacuation of concentration camps.

Shortly after arriving in Flossenburg, Faigla and the other women and girls were loaded into cattle cars and transported to their final concentration camp: Bergen Belsen, located between the villages of Bergen and Belsen in northern Germany.

Faigla remained at Bergen Belsen until it was liberated by British troops at the end of April 1945.

Another girl, the now renowned Anne Frank, was also in Bergen Belsen when Faigla was there. Anne Frank and her sister Margot Frank arrived at the camp from Auschwitz in 1944. Both of them died of typhus just weeks before Bergen Belsen was liberated.

There were more than 60,000 prisoners present when British soldiers entered Bergen Belsen in April 1945. Faigla heard people yelling that the gates were open and she remembers hearing other prisoners yelling at them, telling them to run.

“I did run,” she said, “but once I got out of the gates, I didn’t know where to go or where I was, much less who I was.”

With nowhere else to go, Faigla returned to the camp that was filling with British soldiers. Soon, she recalls, volunteers with the Red Cross began arriving as well.

“They gave them peanut butter,” Lindenbaum said. “My mother ate peanut butter straight from the container.”

Shortly after liberation, Faigla became very ill with typhus and was admitted into the hospital.

Many prisoners died in the months after British troops entered Bergen Belsen, primarily from living for so long in overcrowded quarters, poor sanitary conditions and the lack of adequate food, water and shelter – some 13,000 of them, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The spread of typhus was so rampant that British forces burned the entire camp down to prevent the disease from spreading. In turn, they set up a Displaced Persons Camp, or DP Camp, nearby that became the largest of its kind in Germany.

While Faigla was still in the hospital recovering from typhus, her only surviving brother, Motek Fischel, began searching for her. After receiving a report that she was in a hospital near Bergen Belsen, he finally found her, she said, and told her she could live with him instead of returning to the Displaced Persons Camp.

“My brother found me, and he helped me. He was all I had left.”

One of Faigla’s sisters also survived, but she didn’t know that for some time. Later, Faigla would receive notification that her sister was still alive.

In 1947 Faigla met Berl Moncznik at the Weiden Displaced Persons camp, where she herself lived for a short time. The two began a courtship and the following year were married at the Prinz Albrecht Hall in Munich, Germany, on May 27, 1948.

Shortly after wedding, the couple left Europe and immigrated to Israel where their daughter Penny (now Penny Lindenbaum) was born.

It was during her early years in Israel, Lindenbaum said, that she became aware her family was different, that something bad had happened to her parents.

It was years before the full extent of the horror her parents had experienced came to light, Lindenbaum said, but once she began receiving answers to her questions, the answers frightened her.

“I just thought it was unbelievable,” she said. “That people could hurt my parents for no reason, they did nothing wrong.”

The children of Holocaust survivors, sometimes called second generation Holocaust survivors, suffer alongside their parents but often they don’t show it. They suffer alone.

According to a study conducted by The American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress, the children of Holocaust survivors are more likely to experience symptoms of post traumatic stress and depression.

The study also indicates the second generation survivor is more susceptible to the effects of trauma and carries the burden of destruction while suffering in silence. This can lead to separation anxiety and difficulty in expressing feelings.

Lindenbaum’s experience seems to reflect those findings.

“Listening to my mother speak of her horrific ordeals is extremely painful” Lindenbaum said. “I separate myself as a defense mechanism, and I became a listener rather than a daughter.”

Lindenbaum’s home growing up was a loving one, she said, but her parents weren’t very affectionate; love wasn’t overtly demonstrated. She remembers her father as being her caretaker. Even as she got older, she said, it was her father who took her shopping and made sure she had what she needed.

Even so, she stayed close to her mother during her tender years and rarely left her side.

“I became protective of my mother at an early age, but I was also very insecure,” Lindenbaum said. “I was very clingy, not wanting to leave my mother’s side for fear of losing her.”

The Moncznik family settled in the Bronx, a borough of New York City, after moving to the United States. They lived there until Berl Moncznik died in 2008. Faigla Moncznik, now 88 years old, resides in New Jersey. Penny Lindenbaum married and moved to California until she retired and the Lindenbaums took up residence in Santa Clara.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

Crematorium oven located at Bergen-Belsen seen by British troops entering camp, Bergen Belsen, German, April, 1945 | Public domain photo, St. George News Bergen Belsen concentration camp, Bergen Belsen, Germany, April 1945 | Public domain photo, St. George News Pearl Lefkovit, Faigla Moncznik's aunt who did not survive the holocaust.

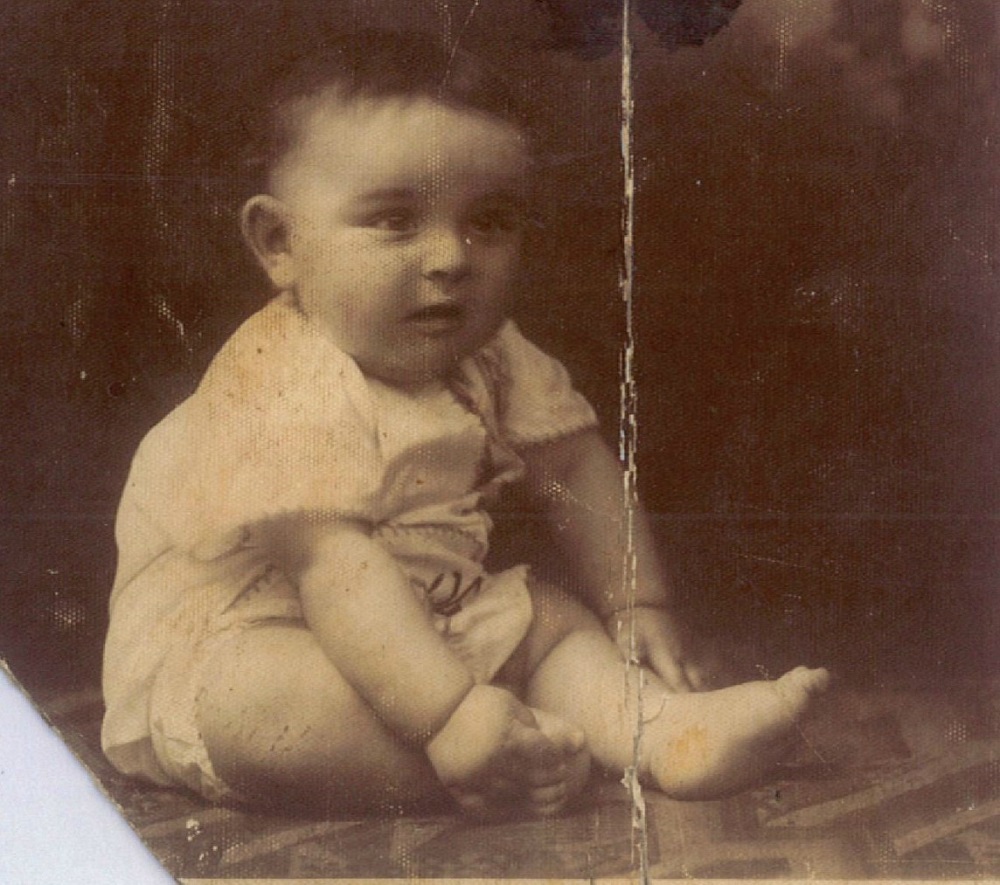

Bedrin, Poland, circa 1930s-40s | Photo courtesy of Penny Lindenbaum, St. George News Faigla Fischel and Berl Moncznik on their wedding day, Munich, Germany, May 27, 1948 | Photo courtesy of Penny Lindenbaum, St. George News Faigla and Berl Moncznik in later years, location and date not specified | Photo courtesy of Penny Lindenbaum, St. George News Faigla Fischel (Moncznik), far left, at a relative's wedding in Poland circa 1930s | Photo courtesy of Penny Lindenbaum, St. George News Chaim Lehman, Berl Moncznik's nephew, deported to Auschwitz in August 1942, along with his mother, Basia, and sister Miriam, where all three died, Niwka, Poland, January 1942 |Photo courtesy of Penny Lindenbaum, St. George News Stone in front of Bergen Belsen concentration camp, Bergen Belsen, Germany, May 5, 2016 | Public domain photo, St. George News Women in a dorm of Bergen Belsen concentration Camp after liberation, Bergen Belsen, Germany, April, 1947 | Public domain photo, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2016, all rights reserved.

A well-done reminder of the greatest tragedy of the 20th century. When people today casually use the terms Holocaust or Nazis, many of them have no idea what they’re really talking about. Neither of these terms should be used lightly and people who do use them should be challenged about what they really know about the history.

One thing they don’t like ever brought up is why hitler and most of germany wanted to get rid of the jews. There are reasons that jews were expelled from more than 100 countries over the centuries before anyone had ever even heard of a ‘nazi’. Also we shouldn’t forget the millions and millions of russian and ukrainian people who the communist bolcheviks (whose leadership were of a vast majority jews) wholesale slaughtered, and holocausted. The jews do not have a monopoly on suffering, and 70+ years on, this cow has been milked to death.

You are right about millions of others over time being persecuted, including persecutions perpetrated by Christians. Have you considered writing your own story about this?