FEATURE – The landscape of Valley of Fire in Nevada is 90 miles south of St. George and only 56 miles northeast of Las Vegas, but it’s a world away from the glitz and glamour of The Strip in many respects. In fact, it has served as the backdrop for other planets, including Mars, in blockbuster movies.

The 40,000-acre park makes a nice side trip for anyone visiting Sin City, and a nice day trip from St. George, offering nature’s red rock masterpieces with its crooks, crags, arches and alcoves – a vast expanse of scintillating scenery.

It is hard to believe that Valley of Fire was once underwater as part of an inland sea, and then, at one time, looked like the Sahara Desert. The park’s red Aztec sandstone formations are products of complex uplifting and faulting – remnants of shifting sand dunes from the Jurassic Period (150 million years ago) left behind after the inland sea subsided and the land arose.

The earliest human inhabitants of the area date back to approximately 300 B.C., the park’s many petroglyphs are the evidence of their presence. It is thought people of the Basketmaker culture carved these pictures in the stone starting about 2,500 years ago. Next came what is known as the Early Pueblo culture followed by the Paiute tribe, who were present when Mormons started to colonize the area at the nearby farming and ranching town of St. Thomas.

Mormons weren’t the first whites to see the area though, according to the 2010 Park General Management Plan, as fur trappers such as Jedediah Smith passed through and the Spanish Trail, widely used in the 1830s and 1840s, meandered near the park. That trail, which later became known as the Mormon Road, became the main route from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles.

White immigrants traversing this trail caused contentions with the Paiutes, especially over ownership of animals and land as the white settlers’ farming activities began to displace the area’s native inhabitants.

A legend surrounding one of the area’s most infamous Paiute Indians led to the name of one of the park’s popular landmarks. This Paiute, known as Little Mouse, was renegade to the white settlers and even an outcast among his own tribe. The story goes that one night Little Mouse fired on an Indian camp after a night of drinking and was locked up then ferried across the Colorado River into Arizona. Allegedly, he escaped and killed two white prospectors and sought refuge from his pursuers in the Valley of Fire. Lawmen conducted several searches to try to bring him to justice with no success because of the Valley of Fire’s rugged landscape.

They were perplexed as to how the Indian could remain in the Valley for so long with no water running through it. The reason was he found a natural depression in the rock landscape that could hold rainwater for months. This little pool, not surprisingly, became known as “Mouse’s Tank” for its service in keeping its benefactor away from the clasp of the law. In the summer of 1897, however, law enforcement found their “Mouse” and ordered his surrender, but he would not give in to their demands and engaged them in a one-hour gunfight in which he was eventually shot and killed.

For a time there was a mining operation in the area for minerals such as borates, gypsum, lithium and silica but the future park itself did not boast significant enough deposits to mine it intensively.

The development of the new park

In the late 19th century, Valley of Fire became a cutoff for a wagon road into Las Vegas. In 1914, a road was built through Valley of Fire as part of the Arrowhead Trail, a highway that connected Los Angeles to Salt Lake City. An American Automobile Association official named the park in the 1920s after traveling through it just before dusk, saying the way the sun shone on the sandstone enhanced the colors, giving the sensation that the rocks were literally on fire.

Some argued that the main road should go through the Valley of Fire, believing that it would eventually become a national park, making the road a no-brainer for the U.S. government. In 1925, however, the idea of the main road through the future park was abandoned when a route farther north, the future path of Interstate 15, was found more suitable and replaced it.

It was during this time period that government officials, chiefly Nevada Gov. James Scrugham, who became a major champion of the park, recognized the future park’s recreational potential. In 1925, the Nevada Legislature authorized the exchange of approximately 8,500 acres of federal land to become a state-owned recreation area, followed by another 27,000-acre swap in 1931.

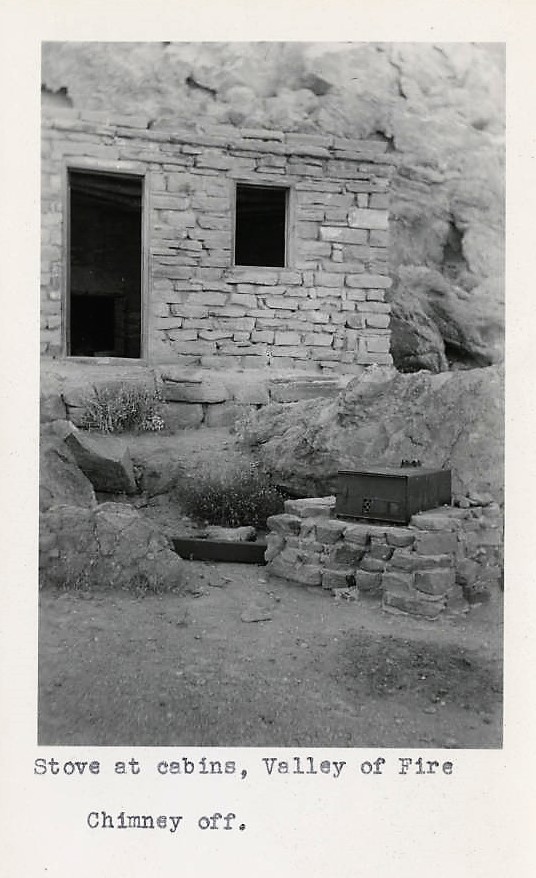

The New Deal was kind to the park as the Civilian Conservation Corps built the park’s first facilities and campgrounds in 1933. Some of these structures included stone cabins to accommodate overnight guests, ramadas for shade and some of the park’s trails. Valley of Fire was formally opened as Nevada’s first state park in 1934, but it took until May 1935 when the state legislature met for it to receive that official legal distinction. In 1934, the highway through the park became a loop road so motorists could drive through without having to see the same scenery twice.

After the CCC’s heyday, appropriations for the park were meager and discontinued completely during World War II, which looked like it could be the death knell of the park and the whole Nevada state parks system.

Almost a national monument

In 1922, Nevada state Sen. E.W. Griffith attended the National Park-to-Park Highway Convention in Sacramento, California, to tout Valley of Fire as a national monument in his promotion of the Arrowhead Trail as a link in the Park-to-Park Highway. His efforts bore fruit and the convention was keen on the idea, recommending that it become part of the national park system.

A 2009 Moapa Cultural Resources Report put together by the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Department of Environmental Studies said that in January 1934 Las Vegas Review Journal Editor A. E. Cahlan said Valley of Fire “has all the elements necessary for a national park.”

In 1939, Scrugham, then a congressman, initiated a campaign for the federal government to take over Valley of Fire and make it part of the Boulder Dam Recreation Area.

“The state is without facilities to develop the attraction,” Scrugham told the Moapa Valley Chamber of Commerce, the cultural resources report stated.

The former governor, then congressman, went on to say that he felt transferring the area to the park service “by legislative enactment” could be done fairly easily.

Interestingly, discussion on the issue stalled when, according to National Park Service maps, it was discovered that some of the park’s most scenic areas, including Atlatl Rock and its Petrified Forest might not have been included in the lands exchanged in 1931. Forging onward, the Park Service presented a bill to Congress to establish a national park in the Boulder Dam area that would include Valley of Fire.

In 1941, the Baker Act ironically sought to eliminate the Valley of Fire from the state parks system, concluding that it had no recreational value, was isolated and inaccessible, but the action was shelved with the outbreak of World War II.

Transferring Valley of Fire to federal control within the Boulder Dam Recreation Area was still being considered in 1948, but opposition by prominent Nevada leaders, including Gov. Charles Russell, effectively ceased talk of any more land exchanges between the state and federal governments. Russell reactivated the State Park Commission in 1952 and worked to stimulate it with state Legislature appropriations to bolster the park, leading to the hiring of its first superintendent and ranger and the improvement of park facilities. In 1955, the Park Commission unanimously voted to retain Valley of Fire as part of the state parks system and cancel any pending applications for land exchanges.

Movie filming location

Since the 1920s, Valley of Fire has hosted numerous Hollywood production companies filming movies of a variety of genres, from western to science fiction. While many of the films could be considered forgettable, there were several that became blockbusters and are still within the public consciousness today.

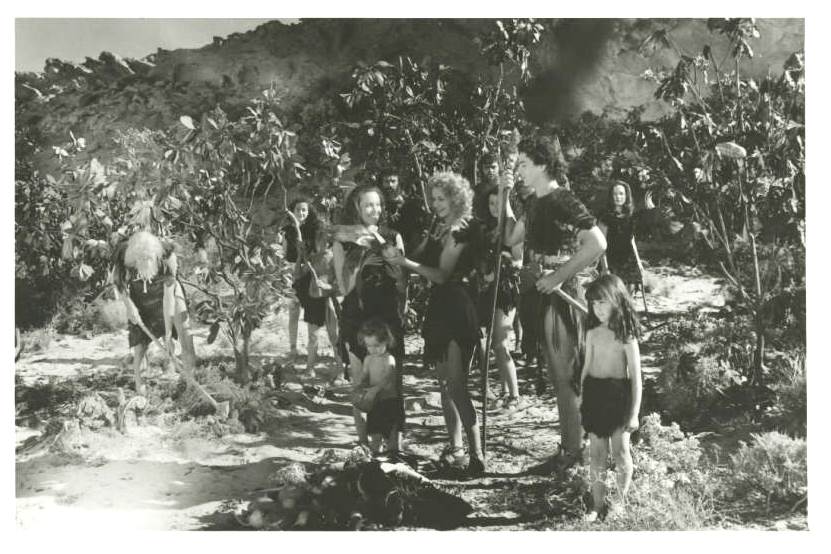

One of the first more famous movies to be filmed on location among the park’s picturesque red rock was the caveman epic “One Million B.C.,” which, excluding roll-over receipts from “Gone With the Wind,” was the top-grossing film of 1940.

In 1963, the park played a prominent role in racing scenes at the end of Elvis Presley’s “Viva Las Vegas” and in 1966’s “The Professionals,” a western starring Burt Lancaster, it was a stand-in for Mexico. The remains of a wall of a set piece from that movie can be seen along the White Domes Trail.

In the 1990s came the park’s sci-fi turn, doubling as the surface of Mars in the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle “Total Recall” the seventh biggest grossing movie of 1990. It also took a turn as the fictional planet Veridian III from “Star Trek Generations” – the film that brought the original Star Trek and Next Generation casts together and was 15th place for box office receipts in 1994. Due to the movie’s plot, Valley of Fire can claim the distinction of being the actual location of death of legendary Star Trek character Captain James T. Kirk, played by William Shatner, at the park’s Silica Dome, accessed via the park’s scenic drive.

Visiting Valley of Fire

Valley of Fire is located just under 90 miles south of St. George by taking I-15 south to Exit 93 and turning onto state Highway 169 towards Logandale and Overton. Pass through both towns and take a right at the Valley of Fire Highway south of Overton towards the park entrance.

A great place to start a trip to Valley of Fire is at the park’s Visitor Center, which provides displays about the park’s ecology, history and geology as well as rangers who can answer any questions. Two of the most popular trails are Elephant Rock and Petroglyph Canyon (Mouse’s Tank is at its end), which are short and easy – ideal for all ages. An excellent picnic spot is the Seven Sisters area, with plenty of picnic tables, ramadas for shade as well as plenty of places to climb around on the inviting red rock spires and their surroundings. Visitors will do themselves a disservice if they do not take a drive along the park’s up-and-back scenic drive to view its otherworldly landscape.

Read more: Explore: Walls of petroglyphs, rainbow-colored rocks showcased at Valley of Fire.

The best times of year to visit are late fall, winter and early spring as summer temperatures are scorching.

For more information about visiting the park, visit its website.

Ed. note: This piece originally published Dec. 3, 2017.

Photo gallery follows below.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people, places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

For previews on Days Series stories, insights on local history and information on upcoming historical presentations, please “like” Wadsworth’s author Facebook page.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

The scenic drive in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This historic photo shows Dave Conger with his children in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, 1920s or 1930s | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows a stagecoach hold up scene being filmed at the north end of Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, circa 1925-29 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows a stagecoach hold up scene being filmed at the north end of Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, circa 1925-29 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This is an image of a historic postcard of Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, 1931 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows a man standing next to the Atlatl Rock Petroglyphs, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, April 20, 1935 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows one of the stone cabins built by the Civilian Conservation Corps and a stove in front of it, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, circa 1935-1940 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows a movie production unit working on the film "One Million B.C." in Valley of State Park, Nevada, 1936-1937 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows a movie production unit working on the film "One Million B.C." in Valley of State Park, Nevada, 1936-1937 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows a scene from One Million B.C. filmed in Valley of State Park, Nevada, 1936-1937 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows Lon Chaney, Jr. filming "One Million B.C." in Valley of State Park, Nevada, 1936-1937 | Photo courtesy of University of Nevada Las Vegas Special Collections, St. George News

The Valley of Fire State Park entrance sign, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The beginning of the Elephant Rock Trail, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

View of Elephant Rock, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

View from the Elephant Rock Trail looking north, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Seven Sisters area, an ideal picnic and bouldering spot in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The scenic drive in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The scenic drive in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The scenic drive in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Sign standing at the trailhead of the Petroglyph Canyon Trail depicting what some of the petroglyphs along the hike could mean, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Panel of petroglyphs in Petroglyph Canyon, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Panel of petroglyphs in Petroglyph Canyon, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Panel of petroglyphs in Petroglyph Canyon, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada, March 15, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews