FEATURE — Previous to 1968, the Kolob Canyons section of Zion National Park was one of the most difficult scenic areas to access in Southern Utah, but after a road was completed that year, it became one of only three national parks in the country with direct access from a major interstate. While these fingers of Zion may be lesser known than the main park, the area has its own rich history.

Drivers don’t notice this astounding set of monoliths from Interstate 15. To see them, one must exit the interstate to the east, drive up the scenic road to the initial climb’s crest and veer right where they come into view.

“You come around the corner and ‘Wow!’” said Tom Haraden, Zion National Park’s former assistant chief of interpretation. “Some people drive I-15 for years and have no idea Kolob Canyons is there.”

Mormon settlers named the area Kolob – which means “Nigh unto the Gods” – because looking at the majestic sandstone cliffs, especially from New Harmony, they must have felt like they were near God.

However, the Mormons weren’t the first to explore the area. The exploration party of Spanish monks Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Veley de Escalante came through in October 1776. Some say these monks – like today’s drivers on I-15 – were too close to the eastern edge of the valley to notice the monoliths, but Rendall Seely, a seasonal ranger in Kolob since 2009 who has researched the area’s history extensively, begs to differ.

One of the monks’ campsites offered a great view of Horse Ranch Mountain and another monolith, Seely said, but they never wrote about the landscape in their journals because they were in survival mode, just having decided to return to Santa Fe instead of moving forward.

“It makes sense they didn’t describe the two peaks,” Seely said. “They had other things on their minds.”

Famed mountain man Jedediah Smith came through in September 1826 along the base of the Pine Valley Mountains – a vantage point that would have offered a stellar view of Kolob Canyons – and down the Black Ridge, but Smith only said the landscape had an “unwelcome appearance” and that the “detached hills” on the east are “somewhat higher.”

In 1854, to go along with the settlement of Cedar City and Parowan, Mormon settlers established an Indian mission and farm called Fort Harmony just east of present day New Harmony, giving settlers a sweeping view of Kolob Canyons.

The secretary of the mission, Thomas D. Brown, wrote the following of Kolob Canyons:

What lofty spires! What turrets! What walls! What bastions! what outworks to some elevated Forts! What battlements are these? What inaccessible ramparts? From these no doubt is often heard Heaven’s artillery cannonading.

LDS apostle and future church president Wilford Woodruff provided the first written account of anyone venturing into Kolob Canyons. In his journal, Woodruff writes of fishing in Taylor Creek, which he called Battle Creek, and engaging in an apparent pastime of Mormon settlers that would have drawn the ire of today’s National Park Service staff: rock rolling.

Woodruff writes of he and two companions rolling the equivalent of about 50 tons of rock. One rock in particular he estimated at five tons.

“It fell about 200 feet perpendicular, struck a shelf of rock and took the shelf with it,” he wrote. “It landed in the creek and sent a shot of water about 50 feet into the air. We made a good deal of thunder for a while.”

One of the legends associated with Kolob Canyons is that it served as a hideout for the scapegoat of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, John D. Lee.

Some say Lee built a cabin on the banks of a nearby creek in the 1860s to hide from federal marshals. Legend has it that he would ride his horse to the ridge where the Kolob Canyons scenic drive currently runs and use his brass spyglass to see if there were clothes on the line of his house in New Harmony. If there were clothes on the line, it was safe to come home, but if there were not, it was time to go back to his cabin. The hiding place was apparently a safe one, as the marshals, who had offered a $5,000 reward – the equivalent of about $140,000 today – for his capture, never found him there.

However, there seems to be some discrepancy where exactly Lee stayed while in Kolob Canyons.

“It is possible that John D. Lee spent some time at Taylor Creek after his involvement in the Mountain Meadows massacre in 1857,” a 1976 National Park Service management plan states. “The remains of a rock chimney in the area may have been part of Lee’s hideout.”

One of Lee’s journal entries talks about cleaning up in the waterfall at the end of what is now the Taylor Creek Trail as well, and Lee’s Pass in Kolob Canyons bears his name.

There are accounts of Lee shooting a rattlesnake and losing his revolver while coming up LaVerkin Creek, Seely said, and there is speculation that it was Lee who gave the area the name Kolob. However, he said, from all the research he’s done there is no secret location of Lee’s hideout identified – nothing found or concretely documented.

“I wish there was,” Seely said.

What is documented are the forays into Kolob of two famous early national park advocates: William Henry Jackson and Thomas Moran.

Most explorers saw Kolob Canyons before they saw Zion Canyon, Seely said. Jackson, an artist and photographer whose later photographs helped convince Congress to set aside Yellowstone as the first national park, came to Kolob Canyons in January 1867 with his companion Bill Crowl and made a few sketches – the first ever made of Kolob.

“In the canon (sic) that Ash Creek flows were some magnificent Red Buttes, apparently two or three hundred feet high,” Jackson wrote in his journal. “Made two sketches of it from the road. Bill & I took a run up into the canon (sic) & made a sketch there. Very romantic spot.”

In 1873, renowned explorer John Wesley Powell hired western artist Thomas Moran to sketch the Grand Canyon and Zion Canyon. Moran ventured up Taylor Creek and sketched Tucupit Point, which he named Colburn’s Butte after his traveling companion, New York Times writer J.E. Colburn.

When Moran returned to the East, he made a woodcut of the scene, which was published in The Aldine, a monthly arts journal, in 1874. The editor of the journal had the following to say of Moran’s piece:

Here are first seen those wonderful masses of red sandstone that, a little further south, become overwhelmingly stupendous, staggering belief in their vastness and magnificent forms. The butte in the illustration is two thousand feet high, and of brilliant hue. It is equally grand and beautiful in storm or sunshine.

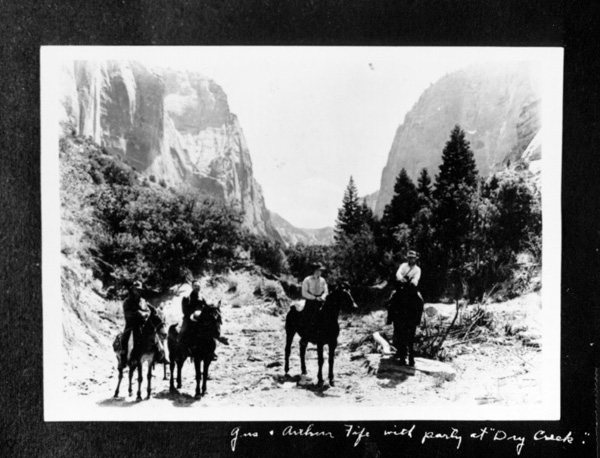

Sam Pollock and his brother Henry Pollock and their families were the first to live close to Kolob Canyons. They lived and dry-farmed in the area at the mouth of Taylor Creek Canyon starting in 1915. Later, three homesteaders – William Palmer, Gustive (Gus) Larson and Arthur Fife – used the Pollock Farm as their way stop and a place to keep the horses they used to get to their homesteads up Taylor Creek Canyon.

Palmer, a stake president for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Parowan, was the first on the scene, building a cabin in 1929 near the current Taylor Creek Trailhead. Fife, a Branch Agricultural College (now Southern Utah University) geologist and city engineer, and Larson, a seminary teacher, built their cabins farther up the creek in 1930, dragging logs to the site by horse. The Larson and Fife cabins are now part of the scenery hikers see along the Taylor Creek Trail.

The trio tried to make good on their homesteading claims, building the dwellings and also fences for the cattle they grazed in the area. They didn’t live on their claims full time, however, as was required for homesteaders. Their cabins served only as shelters when they came up in the summer.

Palmer’s son Rodney said he felt like the reason his father and his friends homesteaded in the area was to keep their teenage sons busy and out of trouble. Rodney Palmer spent an entire summer up the canyon building fences.

Fife abandoned his claim in 1935 when he took a job in the soil erosion service of the U.S. Interior Department on the Navajo Reservation, and Larson had to leave his claim temporarily from 1936-39 when he served as president of the LDS church’s Swedish Mission. When he returned and tried to lay claim to the land again, he found out it was now within the boundaries of the new Zion National Monument, declared by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration in January 1937.

In a case of eminent domain gone awry, the homesteaders received no government compensation for the takeover of their homesteading claims, as they hadn’t lived on the land long enough. Seely said they were happy that it was preserved but were sad they weren’t a part of it. Congress incorporated Kolob Canyons into Zion National Park in 1956.

One of Kolob Canyons’ most notable landmarks is the Kolob Arch. Noted Zion historian and former ranger J.L. Crawford was the first person to take a picture of the arch in 1949. An article in the January 1954 issue of National Geographic published the first picture of the arch, helping it gain some notoriety. Once thought to be the longest-spanning natural arch in the world, the Natural Arch and Bridge Society now considers it the sixth longest natural arch in the world.

The current visitor center at Kolob Canyons was constructed in 1984 with major funding raised by the Zion Natural History Association, now known as the Zion Forever Project. Seely said that numerous visitors show up at the Kolob Canyons Visitor Center thinking they’re in Zion Canyon and are disappointed when they find out they’ve got to drive another hour to reach the most popular part of the park. Other visitors drive down I-15 and have no intention of visiting the park but see the sign marking Kolob Canyons and visit out of sheer curiosity.

Kolob Canyons used to be a much less crowded option for viewing Zion. In 2009, when Seely first started as a seasonal ranger, he said visitation was half what it is now. On busy weekends and major holidays, Seely said, visitors drive around just seeking a parking area.

Seely said the proliferation of information about Kolob on the internet means the secret side of the park is gone.

“If you want solitude, come in the dead of winter,” he said. “It’s really busy in the summer.”

Visiting Kolob Canyons

Kolob Canyons is easily accessible off Interstate 15 Exit 40.

Early in the morning and later in the evening are perfect times to visit as the sun’s rays light up the monoliths’ color in richer hues. If you only have a few hours, drive up the scenic drive and stop at the viewpoint to take in sweeping views of points of interest such as Shuntavi Butte and Timber Top Mountain.

The 5-mile scenic road through Kolob Canyons was part of the Mission 66 program, which heartily increased development in the parks around the National Park Service’s 50th anniversary in 1966.

One plan called for a road up Taylor Creek with a campground at the end, which never came to fruition and never will since much of the area of the Taylor Creek Trail is now designated as wilderness.

Built around the same time were two of the major trails in the area: the 2.7-mile Taylor Creek Trail and 7.2-mile trail from Lee’s Pass to Kolob Arch.

Taylor Creek Trail offers fantastic views of orange-hued monoliths, a peek into the Larson and Fife cabins and the Double Arch Alcove at its end. The hike includes numerous creek crossings so prepare to get your feet a little bit wet.

The most adventurous and strenuous hike is the trail to Kolob Arch, which features several swimming holes on LaVerkin Creek along the way. The trail can be combined with the Hop Valley Trail, whose trailhead is along the Kolob Terrace Road, for a one-way trail seeing different scenery the whole way, but a shuttle car would be needed to complete this route.

The Kolob Canyons’ other trail, Timber Creek Overlook, whose trailhead is at the end of the scenic drive, was built in 1995. The overlook is at the end of a nonstrenuous hike that offers different views of the monoliths as well as a peek into Zion’s southern, more visited section.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

Kolob Arch, Kolob Canyons, Zion National Park, Utah, June 6, 2010 | Photo courtesy of the National Park Service, St. George News John D. Lee.

photo date and location not specified | Photo courtesy of the Washington County Historical Society, St. George News Noted 19th century landscape artist Thomas Moran's slightly exaggerated sketch of Kolob Canyons as it appeared in the magazine The Aldine in 1874. It was the outside world's first view of what would eventually become Zion National Park, photo date not specified | Photo courtesy of Southern Utah University Matheson Special Collections, St. George News Larson and a party on horseback at the base of Tucupit Point, the monolith Thomas Moran sketched for The Aldine, circa early 1930s | Photo courtesy of Southern Utah University Matheson Special Collections, St. George News Gus Larson posing by his new fence on his homestead up what is now the Taylor Creek Trail in Kolob Canyons, Zion National Park, circa early 1930s | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News Gus Larson posing in front of his newly built cabin, Kolob Canyons, circa early 1930s | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News L-R: Gus Larson and Arthur Fife exploring what became Kolob Canyons on horseback, circa early 1930s | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News Gus Larson (middle left) and Arthur Fife (far left) exploring what became Kolob Canyons on horseback with guests, circa early 1930s | Photo courtesy of Southern Utah University Matheson Special Collections, St. George News Virginia Larson, an accomplished pianist who would play for silent movie showings in Cedar City, rode her horse up the canyon to her family's cabin up Taylor Creek on weekends during the early 1930s | Photo courtesy of Southern Utah University Matheson Special Collections, St. George News Virginia Larson, wife of Gustive Larson, posing at the cabin along the MIddle Fork of Taylor Creek, circa early 1930s | Photo courtesy Southern Utah University Matheson Special Collections, St. George News The Larson Cabin, restored by the Park Service in 2009, stands as a reminder of homesteading efforts in the early 1930s, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The Gustive Larson Cabin stands in a wooded area along the Taylor Creek Trail with red-hued monoliths towering over it, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The Gustive Larson Cabin stands in a wooded area along the Taylor Creek Trail with red-hued monoliths towering over it, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The Arthur Fife Cabin, cabin farthest up the Taylor Creek Trail, Zion National Park, Utah, unspecified date | Photo courtesy of Rendall Seely, St. George News View of what have become known as the Kolob Fingers from near New Harmony, Utah, a view that entreated New Harmony residents past and present but also a view I-15 drivers cannot see from the freeway, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Sam El Halta, St. George News Kolob Fingers as seen from the air, Zion National Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Lin Floyd, St. George News The entrance sign of the Kolob Canyons section of Zion National Park, patterned after the one the Civilian Conservation Corps built at the South Entrance Station, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The Kolob Canyons Visitor Center, built in 1984 with money raised from the Zion Natural History Association (now known as the Zion Forever Project), Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The first view of Kolob Canyons' monoliths drivers see along the 5.2-mile Kolob Canyons Scenic Drive, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The Taylor Creek Trailhead, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News Monoliths framed by trees along the Taylor Creek Trail, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News Monoliths framed by trees along the Taylor Creek Trail, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News Views along the Taylor Creek Trail, Zion National Park, Utah, April 2017 | Photo courtesy of Brian Fuller, St. George News The evening sun bring out rich color in the monoliths seen from the Taylor Creek trailhead, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The glow of the evening sun on monoliths near the middle switchback of the Kolob Canyons Scenic Drive, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News Paria, Middle and Beatty points, as seen from the viewpoint at the end of the Kolob Canyons Scenic Drive, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News Nagunt Mesa and Timber Top Mountain as seen from the viewpoint at the end of the Kolob Canyons Scenic Drive, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News The view of Timber Top Mountain and Shuntavi Butte from the end of the Kolob Canyons Scenic Drive, Zion National Park, Utah, May 19, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah, inviting readers to explore these aspects of the region on a day trip.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2019, all rights reserved.

Great story on a wonderful area….just don’t let the “Mighty 5” start a advertising blitz on this, otherwise we locals will have yet another National park to busy with damn tourists to ever visit