FEATURE — It’s a natural amphitheater, not a canyon.

Utah’s second national park, a stunning showcase of erosive forces that formed colorful rock pinnacles and spires known as hoodoos, has always had somewhat of an identity crisis.

In the early 20th century, some referred to it as “Temple of the Gods,” but that was too close to “Garden of the Gods,” just west of Colorado Springs. Others called it “Bryce’s Canyon” as if its namesake — who only made his home in the area for approximately five years — owned it.

Back in 1920, the Utah State Automobile Association staged a contest to rename it, concluding that its name was too common for a place so grand.

Garfield County, however, put up a fuss, saying it should have the most say in the naming of its best attraction. The contest went on undaunted, however, but in the end, its judges felt that the names submitted by its entrants weren’t up to par and scrapped the rebranding idea in favor of keeping it Bryce Canyon.

Even though the park’s name is a misnomer, visitors don’t seem to mind as they stroll along the rim of its main amphitheater.

Early human contact

Paiutes and their ancestors have roamed the area for centuries, and settlers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were the first Euro-Americans to see its grandeur in the 19th century.

In the early 1870s, members of the Wheeler Survey, a government corps sent to explore and map the western U.S. west of the 100th meridian became the second set of European Americans to gaze atop what one member of the survey, Grove Karl Gilbert, called “The Summit of the Rim,” as he described it in his diary.

“Just before starting down the slope we caught a glimpse of a perfect wilderness of red pinnacles, the stunningest thing out of a picture,” Gilbert wrote, as quoted in a Historical Resource Study about Bryce Canyon by Nicholas Scrattish published in 1985.

One of the most poetic early descriptions of the canyon that’s actually an amphitheater came on Nov. 18, 1876, from U. S. Deputy Surveyor T. C. Bailey.

“There are thousands of red, white, purple, and vermilion colored rocks, of all sizes, resembling sentinels on the walls of castles, monks and priests in their robes, attendants, cathedrals and congregations,” Bailey wrote. “There are deep caverns end rooms resembling ruins of prisons, castles, churches with their guarded walls, battlements, spires, and steeples, niches and recesses, presenting the wildest and most wonderful scene that the eye of man ever beheld, in fact, it is one of the wonders of the world.”

Despite these superlatives from early explorers, neither early LDS reconnaissance nor the 1870s Federal surveys directed much public attention to the Bryce Canyon region during this time period, Scrattish wrote.

“The Mormons did begin settlement near the eastern edge of the park in 1874, but this did nothing to directly popularize Bryce Canyon’s uniqueness,” Scrattish wrote. “To some extent Bryce Canyon’s obscurity, until the second decade of the 20th Century, can be attributed to its distance from railways and sizeable towns.”

In 1875 or 1876, the park’s namesake, Ebenezer Bryce, settled in what was known as Clifton (Cliff town) because of its close proximity to the nearby pink cliffs. He became disenchanted with the settlement and moved upstream along Paria Creek to Henderson Valley, building a 7-mile long irrigation ditch to make farming possible.

“Bryce was also instrumental in building a road to make nearby timber and firewood more accessible,” Scrattish wrote. “Local people began to use the road and customarily called the amphitheater, in which the road terminated, ‘Bryce’s Canyon.’”

Bryce’s motive for moving to the area was due to his wife’s fragile health, but he realized the climate was not as suitable as once thought and moved to Arizona in 1880, at the time not realizing the legacy he would leave on the amphitheater he called “a helluva a place to lose a cow.”

By most accounts, the area’s first settlers were not that impressed with the one-of-a-kind landscape that enveloped them, which completely astounded 20th century chroniclers of Bryce Canyon, Scrattish noted.

“In fairness to these people, it is, perhaps, more just to empathize with the spirit of a different time—to perceive the situation as they perceived it,” Scrattish surmised. “Mormon pioneers in the Bryce Canyon region were an assiduous, God-fearing group, whose struggle against the harsh realities of everyday life left little psychic energy for an appreciation of magnificent scenery.”

In the early 20th century, especially the late teens, Bryce Canyon started garnering attention, significantly aided by its proximity to Zion and the Grand Canyon’s North Rim, which formed a scenic tourist “loop.” Another factor in its popularization was “an uneven but tangible improvement in the area’s roads,” Scrattish noted.

“A sprinkling of Mormon settlements east and northwest of Bryce Canyon brought with them inadvertent explorers of lesser known byways, such as salesmen, were destined to drive some of the first automobiles into Tropic and Cannonville,” Scrattish wrote. “Their accounts of the area encouraged visits by others.”

The Forest Service also played a role in publicizing Bryce’s fanciful landscape.

Forest Service Supervisor J.H. Humphrey enlisted Mark Anderson, foreman of the Forest Service grazing crew, to publicize it. When Anderson saw it for the first time, accounts note that he immediately rode into Panguitch and telegrammed the District Forester in Ogden requesting that Forest Service photographer George Coshen be sent to Bryce Canyon with still and movie cameras to capture the grazing crew working near the amphitheater’s rim. Coshen sent his movie and still pictures to Forest Service officials in the District of Columbia. The pictures were also made available to Union Pacific Railroad officials in Omaha.

Arthur Stevens, another member of the Forest Service grazing crew, wrote a short, illustrated article for “Outdoor Life,” an early Union Pacific publication, in late 1916. Humphrey also dictated an article for Red Book, a Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad periodical, publishing it under a pseudonym. These stories were the first descriptive articles about Bryce Canyon to be published.

In 1917, C.B. Hawley, director of the Utah State Automobile Association visited Bryce Canyon and reported about it to the association’s officers in Salt Lake City. Another director of the organization visited soon after to confirm Hawley’s report and returned with an even more glowing report. These two directors and state Sen. William Seegmiller of Kanab encouraged “Salt Lake Tribune” photographer Oliver Grimes to visit and take pictures.

Grimes’s full-page article, titled “Utah’s New Wonderland,” appeared in the Sunday Magazine section of the “Tribune” on Aug. 25, 1918, and was probably read by more people than anything previously written on Bryce Canyon, Scrattish wrote. The article said the soon-to-be park was now open to automobile traffic and gave explicit directions to it from Panguitch.

The original Ruby

In the spring of 1916, when the Forest Service started publicizing Bryce Canyon, Reuben (Ruby) Syrett and his wife, Clara (Minnie), lived in Panguitch but had been scouting the area to start a ranch. The couple decided to homestead a quarter section near Bryce Canyon, approximately 3.5 miles north of what is now Sunset Point. The story goes that the Syretts were there six weeks before a Tropic rancher introduced them to the amphitheater’s rim.

The sight left them speechless.

Soon the couple started to invite their friends in Panguitch, who thought they were foolish to homestead in such an area, to see the amphitheater. Despite this, the Syretts hung on to their homestead claim and even started to purchase additional land near it.

In 1919 as word started to spread that Bryce Canyon’s beauty was worth a visit, a large group from Salt Lake City came and were accommodated by tents the Syretts set up near Sunset Point. The couple also fed the group lunch.

Later that day, Ruby Syrett brought up five or six beds which he placed under pine trees near the rim. The Syretts fed the group dinner and breakfast the following morning.

“Whether by design or chance the Syretts began accommodating tourists,” Scrattish pointed out. “They remained near Sunset Point until the fall of that year.”

During the spring of 1920, the Syretts decided to build a permanent lodge.

The location of that future lodge was on land set aside as a school section by the state, so Mr. Syrett received verbal permission from the State Land Board to erect the structure. That lodge, known as “Tourist’s Rest,” measured 30 feet by 71 feet and was fashioned of sawed logs and included a dining room with a fireplace, a kitchen, a storeroom and several bedrooms.

“In keeping with the Syrett’s informal nature, the lodge’s double front doors served as a guest register,” Scrattish wrote. “Visitors thoroughly enjoyed carving their names onto the doors.”

The Syretts added 8-10 cabins near the lodge as well as an open-air dance platform. They operated this lodge until it was sold to the Utah Parks Company in 1923 (and a few years later became part of the new park) after which they moved their operation, which they called Ruby’s Inn, to where it stands now, just north of the park’s border.

The Utah Parks Company built Bryce Lodge a few years later.

Utah Parks Company

The Utah Parks Company, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad, was the park’s main concessionaire in its early years. The company transported its guests via a spur off the main line that reached Cedar City and packed them into 12-passenger buses for Grand Circle tours to Zion, the North Rim, Bryce Canyon and Cedar Breaks, with lodges in all four places.

Read more: Parkitecture history day; experiencing the Golden Age of Zion, Bryce Canyon and their lodges

The Parks Company provided special programs for the tourists each night and “wild tales to entertain everyone along the way,” said Fred Fagergren, who served as Bryce Canyon’s superintendent from 1991-2002.

“This was the first effort to promote these parks and represents what would come as Utah began their Big 5 advertisement efforts,” Fagergren explained.

The Grand Circle tour, back in its heyday in the 1920s and 1930s, must have been quite a trip for these early park tourists, according to Fagergren:

When I think of the condition of the roads, the vehicles in which the early visitors rode, the time it would have taken to drive between each of these parks in those slow, pre-air-conditioned buses — the experiences along the roads would have been in stark contrast to the positive experiences once people got to the parks.

Despite the sometimes rough-going on those Grand Circle tours, the Utah Parks Company created an amiable atmosphere with most of its employees being locals who really valued the places where they worked.

“Those connections between local people and the National Parks formed positive bonds and strong friendships that continue to provide support for the National Parks and the environment for years to come,” Fagergren said. “Something that has largely disappeared today, except to the extent the parks provide economic support for the local and state economies”

Even though the Utah Parks Company advocated for good roads for its Grand Circle tours, it was those roads, in part, that signaled its demise. By the late 1940s, ridership on those tours had significantly declined, and they were discontinued. In 1971, the Utah Parks Company dissolved and a new concessionaire took its place.

National Park status

Utah senator Reed Smoot became a huge proponent of turning Bryce Canyon into a national park. His first attempt came in November 1919 but in the spring of 1920 the Secretary of the Interior reported that it would be more appropriate to designate it as a national monument by presidential proclamation rather than getting Congress involved to make it a national park.

The strong recommendations from the departments of Interior and Agriculture resulted in President William G. Harding pronouncing Bryce Canyon as a national monument June 8, 1923.

During this time period, the park gained a powerful Eastern ally in Michigan Congressman Louis B. Cramton, who was the chairman of the subcommittee for Department of Interior appropriations. Cramton had traveled the area extensively and gave a speech to the American Automobile Association lauding the area’s scenic wonders.

As a national monument, the Forest Service administered Bryce Canyon from 1923 to 1928. The Forest Service’s major contribution to the monument during its brief tenure as its manager was the construction of good roads to and within the monument, as well as a campground.

Stephen Mather, the first NPS Director, thought that since Utah already had a national park, it didn’t need another one.

“He was convinced to come to Utah, and there was a concerted effort to convince him that Bryce Canyon should have another National Park,” Fagergren said. “I understand even the LDS church participated in this effort and a number of young women came down as part of that effort.”

Besides the attitude of the Park Service director, there were three other major challenges to overcome before it could become a national park. No. 1, all the land within its proposed boundaries needed to be owned by the federal government, which required the state to relinquish some of its land within the park as well as the Union Pacific to deed land it owned to the Federal government. No. 2, the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway had to be approved, which would provide better access from Zion to Bryce Canyon. Cramton, in his powerful position, would not approve the road unless the terms creating the national park were also approved. The Union Pacific refused to deed its land until the road was approved as well.

No. 3 was a naming issue. The original bill enacted to turn it into a national park named it “Utah National Park,” which was determined to be too nondescript and was, of course ultimately scrapped in favor of the name that had stuck since the 1880s. The state only agreed to relinquish its land within the park if the Bryce Canyon name was retained.

On Feb. 25, 1928, Bryce Canyon officially became a national park, but for the first 28 years of its existence, Bryce Canyon was managed by Zion National Park. The NPS justified this choice because, at the time, the park was a seasonal park, open 6-8 months a year.

“When the Forest Service tended the monument, visitation in the winter was so slight a snow removal program for existing roads and footpaths was discouraged,” Scrattish wrote. “The National Park Service expected this trend to continue, making the need for a separate administration in Bryce Canyon all the more difficult to justify.”

For the first few years, the park only had one ranger on duty, Maurice Cope. First employed by the Utah Park Company to assist tourists at Bryce Canyon Lodge, the NPS hired Cope from May to September starting in 1929. At first, he lived in nearby Tropic and taught school the rest of the year but moved his family to the park in 1931.

Cope became an integral part of the park’s early development.

“I helped to lay out all the trails and roads in the canyon and along the rim,” Cope wrote, as quoted in Scrattish’s history. “We started to hire help to build trails and make ready to build campgrounds, restrooms, chop wood and haul it for the campers, assign the rangers to the checking station, help patrol, look out for those who might violate the rules, look out for forest fires and anything else that needed attention.”

Cope served as a ranger in Bryce Canyon until he transferred to Zion in 1943.

It was during his tenure that local civic pressure to administer the park separate from Zion started at a meeting of the “Associated Civic Clubs of Southern Utah” in November 1934. The NPS still maintained that a joint administration to pool equipment, supplies and personnel was essential with the limited operating expenses

Not surprisingly, visitation skyrocketed after World War II and many parks across the country, including Bryce Canyon, were not adequately prepared to handle such crowds and were overrun.

During the summer of 1955, the Salt Lake Tribune sought to make its readers aware of the deplorable conditions found in Utah’s national parks and monuments through a series of articles. Tribune staff writer Don Howard devoted the second article to Bryce Canyon and interviewed Assistant Superintendent Tom Kennedy, who told Howard the park needed more parking space, more scenic viewpoints, more miles of trails and roads, more campsites, a better museum as well as better information and interpretive services. Joint administration with Zion had done little to improve things.

National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth’s “Mission 66” Program, hatched to help the parks to better accommodate their growing visitation by the 50th anniversary of the agency’s founding in 1966. The program infused much-needed capital into the National Park Service and did much to improve or replace park facilities around the country and improved morale within the agency’s employees. It was a significant reason the split in park management between Bryce Canyon and Zion, which became official July 1, 1956.

The change meant the addition of new park staff, including a chief park ranger, chief park naturalist and an additional park ranger. The Mission 66 program also brought a new visitor center, more employee housing, a modern maintenance yard and upgrades to its campground.

Ruby’s Inn today

Nearly 100 years since Ruby and Minnie Syrett first hosted guests in their “Tourist’s Rest” along the rim, their location just north of the entrance to the park is still owned by their grandchildren with day-to-day operations managed by their great-grandchildren.

The Inn operated independently until the 1970s, when it became affiliated with Best Western. In 1984, the original lodge burned down, unfortunately, but a new one was erected only a year later, said Jean Seiler, Ruby’s Inn Marketing Director. The Western town across the highway from Ruby’s Inn was added in 1987.

In 2000, the Syrett family developed Bryce View Lodge for budget travelers and eight years later built the Bryce Canyon Grand Hotel for luxury travelers. That same year Ebenezer’s Bar and Grill went up, which has become an entertainment and banquet facility. At first, Ebenezer’s hosted a cowboy western show but has since transitioned into a country music show with artists from Nashville, Seiler said.

In 2007, the Ruby’s Inn area was incorporated as Bryce Canyon City, which raised the ire of Garfield County and its commissioners because of the tax revenue the county would lose with the change since Ruby’s Inn is the county’s largest employer. There were accusations that the Syrett family was doing it out of greed, and a story in the New York Times at the time even called Bryce Canyon City a “company town.”

However, Seiler said the antagonism towards the incorporation simmered down fast as Garfield County adjusted its tax levy to make up the difference in lost tax revenue.

According to Seiler, Ruby’s Inn’s motives for incorporating as a town were pure. Until the complex became a city, it was hard to work with government agencies as a private business, he said.

“Now we can cooperate better together,” Seiler said. “Now we’re a gateway town, not a gateway business.”

Seiler said they ensured that Bryce Canyon City and Ruby’s Inn were completely separate entities from the beginning.

Two things Bryce Canyon City has done to help both local residents and tourists alike is develop a Public Safety facility and a staging area for the Bryce Canyon Shuttle.

Bryce Canyon today

Transportation is one facet of Bryce’s history that has influenced it the most and carries some of the most significant ramifications today, Bryce Canyon Visual Information Specialist Peter Densmore said.

The Utah Parks Company’s idea of Grand Circle tours still define the experience for many travelers today. There is a high probability that visitors who stop at Bryce Canyon will do the same at Zion, the Grand Canyon and Cedar Breaks, Densmore noted.

Today, both Fagergren and Densmore said national parks, Bryce Canyon included, are coming full circle and realizing that they need to look at other transportation options to accommodate the growing number of visitors. It’s time for Americans to re-examine their relationship with their cars, Densmore said.

Thankfully, Densmore said the public attitude to mass transportation is changing – the younger generation almost expects it. However, some of the older generation, he noted, come in their large RVs and are more reluctant to leave their cars behind because automobiles were heavily marketed in their day and age, and they cannot shake their love affair with their private car.

In 2000 Bryce Canyon initiated a voluntary shuttle system, the same year Zion implemented its mandatory shuttle. Fagergren, who was superintendent at the time the shuttle started, said it was a “pretty daring move.”

“Unlike Zion, there was no special federal funding to buy buses or any of the other aspects,” Fagergren explained. “We sold the idea to D.C. on the concept that Bryce Canyon was the opportunity to test an idea we thought would work and which would encourage visitors to use the shuttle and reduce the number of cars coming into the park.”

Even though the shuttle is still going strong today, one of the initial concepts initiated at its inception failed miserably. The park tried to implement what today would be referred to as “congestion pricing” in which visitors paid a higher fee to enter the park if they drove their cars in, but those riding the shuttle would pay a lower fee.

“Unfortunately, that concept lasted one day,” Fagergren said. “There were so many complaints that went all the way to the top in Washington D.C. that we deserted the two-fee concept.”

Currently, the Bryce Canyon shuttle stops at the major staging areas along the rim of the main amphitheater, operates from April through October, but Densmore said, like the Zion Shuttle, the season continues to expand. For instance, the park has extended the shuttle’s season by a month as a result in the uptick in visitation.

The park saw 2,679,478 visitors in 2018, which was up by 107,794 visits from year before, and up over 1.6 million visits from 2010.

Even though Bryce Canyon’s shuttle is voluntary, it still has been vital in dealing with the park’s visitor congestion, Densmore said. The reception to the shuttle is generally positive, with many visitors preferring to leave their cars parked and board the bus.

Like many parks, Bryce Canyon is at a crossroads as to what to do to accommodate the rising number of visitors. One of the options is to expand the shuttles’ capacity and routes and possibly make it mandatory, Densmore explained, which doesn’t seem as if it would cause much of a ripple because after visiting Zion, many visitors expect the shuttle to be mandatory.

Bryce Canyon has more challenges than just increasing visitation, however, including infrastructure needs, housing for seasonal workers, deferred maintenance, visitor communication, fire suppression and inadequate staffing.

The Bryce Canyon Natural History Association, the official nonprofit partner of the park, has been a vital partner for the park to help fill its funding gaps.

“We would be in a completely different situation without that partnership,” Densmore said.

The BCNHA has provided over $9 million to help the park and has worked with Ruby’s Inn and Bryce Canyon Lodge help fund-raise for the park. The program allows visitors to add one dollar to the price of each night’s stay that goes directly to the Association to fund some of the park’s needs that are not covered by its annual budget.

Park management will continue to change things up to meet the park’s challenges. The erosive forces of wind, water and ice that carved the hoodoos of the amphitheater will continue to change as well. For instance, the Sentinel, along the Navajo Trail near Thor’s Hammer, succumbed to that erosion in December 2016, and it won’t be the last.

Visiting Bryce Canyon

Bryce Canyon is an approximate 2 hour and 15-minute drive from the St. George area.

To get there, head north on Interstate 15 until Exit 95, then take state Route 20 eastbound to U.S. Route 89. Turn right at U.S. 89 and head south through Panguitch until the turnoff to state Route 12. Make a left and drive east through Red Canyon, a scenic spectacle in and of itself, before reaching state Route 63, then take a right until reaching the entrance to the park.

There are more accommodations in the area than just Ruby’s Inn’s properties, including the nearby towns of Tropic and Panguitch.

There are plenty of activities to do in the park, chief among them is hiking its many trails, including a stroll along the rim of the main amphitheater, but to truly appreciate its many hoodoos, it is essential to descend below the rim on trails such as Navajo Loop, Queen’s Garden and Peek-a-boo Loop.

The busiest tourist area is along the rim of the main amphitheater between Bryce Canyon Lodge and Bryce Point. To see fewer crowds, visitors can hike the Fairyland Loop, whose trailhead is near the north entrance, or head farther south along the road and check out the viewpoints south of the main amphitheater, such as Swamp Canyon, Ponderosa Canyon, Natural Bridge and the two southernmost views of the park, Rainbow and Yovimpa points.

For more information on Bryce Canyon and schedules of ranger-led activities, visit the park’s website.

Photo gallery follows below.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people, places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

This historic photo shows Ruby Syrett, founder of Ruby's Inn standing along the rim of Bryce Canyon's main amphitheater, circa, 1916-1930 | Photo courtesy of Ruby's Inn, St. George News

This historic photo shows Ruby Syrett with horses near the rim of Bryce Canyon's main amphitheater, Bryce Canyon National Park, circa, 1916-1930 | Photo courtesy of Ruby's Inn, St. George News

This historic photo shows Ruby and Minnie Syrett's original "Tourist's Rest" along the rim of the main amphitheater,Bryce Canyon National Park, circa, 1920-1923 | Photo courtesy of Ruby's Inn, St. George News

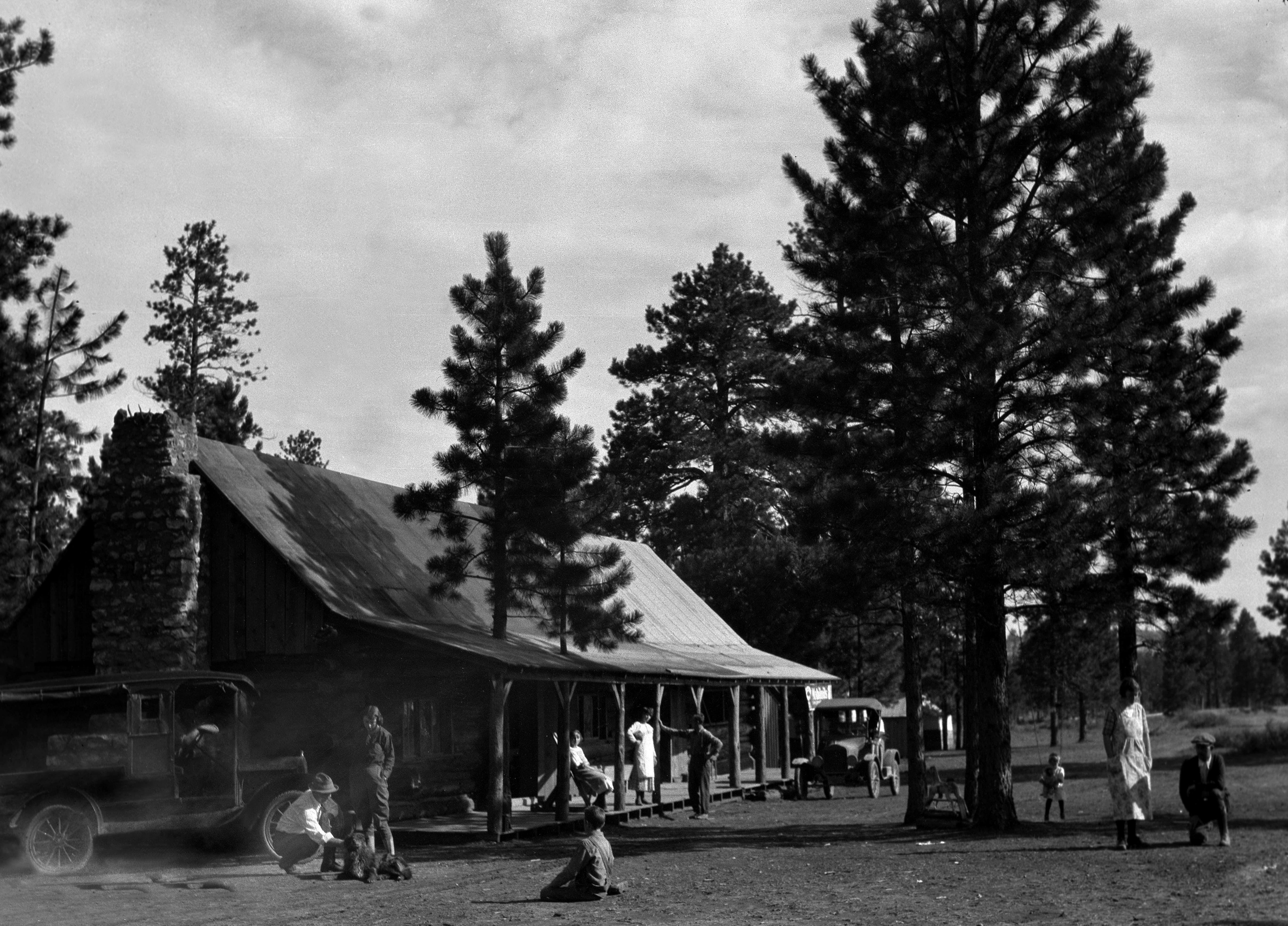

This historic photo shows the original Ruby's Inn after the Syrett's moved their operation just north of the park's entrance, Bryce Canyon National Park, circa 1920s or 1930s | Photo courtesy of Ruby's Inn, St. George News

This historic photo shows Utah Parks Company buses parked near Bryce Canyon Lodge, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, 1938 | Photo courtesy of SUU Special Collections, St. George News

This historic photo shows Utah Parks Company buses parked next to Bryce Canyon Lodge, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, 1938 | Photo courtesy of SUU Special Collections, St. George News

Bryce Canyon's main amphitheater from the air, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Randy Weekes, Sky View Aerial Photography, St. George News

The view of Bryce Canyon's main amphitheater from Bryce Point, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 20, 2011 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The view of Bryce Canyon's main amphitheater from Bryce Point, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 20, 2011 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Hikers descend from the rim on the Queen's Garden/Navajo Loop trail, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Bryce Canyon National Park, St. George News

A horse rider starts the journey along the trail just below Sunrise Point, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 20, 2011 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Looking up towards the rim at the bottom of the switchbacks along the Navajo Loop Trail, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Looking down the switchbacks on the Navajo Loop Trail, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Hikers meander through the switchbacks along the Navajo Loop Trail, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Sentinel along the Navajo Loop Trail near Thor's Hammer, which toppled over in December 2016, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Horses ride along the trail with the Sinking Ship in the background, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Thor's Hammer, one of Bryce Canyon National Park's most iconic hoodoos, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Looking up at the base of Wall Street, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A tree ascends above Wall Street at its base, the bottom of the Navajo Loop switchbacks, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 15, 2016 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Winter view of Fairyland Point, Bryce Canyon National Park, February 2019 | Photo by Hollie Reina, St. George News

Winter view of Fairyland Point, Bryce Canyon National Park, February 2019 | Photo by Hollie Reina, St. George News

Waterfall along the Mossy Cave Trail, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Bryce Canyon National Park, St. George News

View of Paria Point, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Bryce Canyon National Park, St. George News

Ranger giving a presentation about the Grand Staircase along the rim of the main amphitheater, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Bryce Canyon National Park, St. George News

A bus similar to the ones originally used by the Utah Parks Company on display at a special event, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, July 2015 | Photo courtesy of Bryce Canyon National Park, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2019, all rights reserved.