FEATURE — “You know Route 66? It’s still here!”

That was the exclamation of an excited Lightning McQueen as he speaks to his agent over the phone after being discovered by the media while holed up in Radiator Springs in Disney/Pixar’s 2006 animated hit, “Cars.”

The popular movie was largely inspired by its director’s own trip over “The Mother Road,” and some places and characters in the movie are near direct cartoon incarnations of real things along the route.

McQueen was on to something in his announcement to his agent. Route 66 is still here and has seen quite a bit of a resurgence over the last few decades.

In its glory years, the road proved an escape for drivers seeking freedom and adventure on the open road. Today, it provides the same thing for those willing to get off multilane interstates to traverse what’s left of it.

Michael Wallis, author of the 1990 book “Route 66: The Mother Road,” described what became known as “The Main Street of American” in those kinds of terms.

“A thread looping together a giant patchwork of Americana, this fabled road represents much more than just another American highway,” Wallis wrote. “Route 66 means motion and excitement. It’s the mythology of the open road. Migrants traveled its length; so did desperadoes and vacationers. Few highways provoke such an overwhelming response. When people think of Route 66, they picture a road to adventure.”

Northwestern Arizona is home to the longest uninterrupted portion of the historic highway that once stretched from Chicago to Los Angeles, the 159-mile span from Seligman to Kingman. A great starting point for those wishing to explore this stretch is the Arizona Route 66 Museum and Visitor Center in Kingman, where travelers can add context to their journey into a storied past.

The Trailblazers

Native Americans were, of course, the first humans to frequent the area along well-worn footpaths that served as trade routes to the Pacific Ocean for tribes exchanging treasures from all around the West, sometimes using gems, shells, stones and woven baskets as currency. The tribes that have inhabited the area for centuries are the Havasupai, Hualapai and Mojave.

Juan de Onate was the first European of record to visit the area in 1604 and Franciscan missionaries Dominguez and Escalante came through in 1776.

Starting in the early 19th century, free-roamers such as fur trappers and gold-panners wandered in what became Northern Arizona looking for valuable goods and by midcentury, more and more Americans began migrating to the West for what they considered literal greener pastures — the chance to own land.

In 1851, Capt. Lorenzo Sitgreaves arrived and created the first technical map of the area. After months of research, he recommended that a road be built along the 35th parallel rather than along other existing trails. For his efforts, Sitgreaves earned some name recognition along the future route of the “Mother Road” — a 3,652 foot high mountain pass just outside Oatman was named to honor him.

By 1857, the U.S. government wanted to stake out a “winterproof” route to the West and contracted with Navy Lt. Edward F. Beale to survey and develop such a route. True to Sitgreaves’ estimation, Beale foresaw the route following the 35th parallel as closely as possible, which was determined far enough south to provide an all-weather road.

Beale and a crew of 44 men, 12 wagons and 120 animals set out to survey the route. In addition to assorted horses and mules, Beale’s caravan also included 25 camels fresh from Egypt because part of Beale’s assignment included testing camels in the Southwest for consideration for future military use. It turned out to be the U.S. army’s first and last camel brigade. Although the camels performed exceptionally on the journey, they were not adopted for military use for two main reasons: a request for more camels was ignored because of the rising tensions that escalated into the Civil War and many just couldn’t take the camels seriously.

The result of the journey was the Beale Wagon Road, the first federally-funded wagon road in America, built at a cost of $50,000 for an approximately 400-mile road. Sections of the Beale Wagon Road are still visible today and accessible from several points along Route 66.

Pioneers who started out as a trickle and eventually became a steady stream journeying along the route met several difficulties, including finding suitable water, traversing rough trails in rickety wagons, sickness, food shortages and conflicts with Native Americans. Due to those conflicts, in 1859 the army established Fort Mojave on the Colorado River to protect emigrants from aggression from the Mojave tribe.

The original charter for a railroad across the 35th parallel came in 1866 but was not completed until much later. Lewis Kingman (namesake of the Arizona city) of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad surveyed the route from Albuquerque to the Colorado River, where it connected with the Southern Pacific line at Needles, California, in the 1880s.

The railroad provided more freedom and ease for later migrants, getting them to their destinations much quicker and practically without hardship.

“It is no coincidence, then, that U.S. Route 66 represents much of the same freedom as did the railroad at the turn of the century,” a plaque at the Kingman Route 66 museum reads. “Both share common, unspoiled terrain as well as a knack for holding the attention of the curious traveler.”

The railroad parallels portions of Route 66 to this day, and its placement gave motoring Americans their first taste of “riding shotgun” with trains.

The Okies

Formally established in 1926, Route 66 was “a 2,448-mile journey to the heart of America,” the Historic Route 66 Association of Arizona pamphlet reads. “Contrasted with the other highways of its day, Route 66 did not follow a traditionally linear course. Its diagonal path linked hundreds of communities across eight states and became the principal east-west artery.”

At first, much of Route 66 was dirt. It was not paved in its entirety until 1938.

It was on this dirt road that one significant group of people traveled from the Midwest seeking a better life. The combination of economic depression, ill-advised farming practices and severe drought led to the “Dust Bowl” in the 1930s, when extreme storms literally carried the topsoil of farmland hundreds of miles away.

“Dust clouds several miles high blew across the plains, covering everything with fine, dry silt,” a museum interpretive plaque states. “Crops would not grow and animals and humans were actually driven mad by the wind and the dust.”

These harsh conditions inspired farmers who became known as “Okies” because they were centered around the panhandle of Oklahoma to travel west to find their greener pastures. Their principal route became known as the “Mother Road” because of John Steinbeck’s description of it as such in his novel, “The Grapes of Wrath,” which chronicled the travails of a fictional Dust Bowl family.

In Chapter 12 of Steinbeck’s masterpiece, he wrote: “66 is the path of people in flight . . . they come into 66 from the tributary side roads, from wagon tracks and the rutted country roads. 66 is the mother road.”

Interestingly, according to the museum’s interpretation materials, more than 200,000 people fled west to California during the era, but less than 16,000 actually stayed there.

“Prosperity was supposed to be just around the corner, but some made the long trek to California in dilapidated ‘tin lizzies’ only to turn back after finding more poverty and despair,” one museum plaque reads.

The completion of paving the route on the eve of World War II became significant to the war effort. Improved highways were key to rapid mobilization during the conflict. The military chose numerous locations in the West as training bases because of their geographic isolation and good weather. Many were located on or near Route 66, including the Kingman Army Airfield Gunnery School. It was not uncommon to see mile-long convoys of trucks along the road transporting troops and equipment.

The Vacationers

It is from the post-war years that most of the nostalgia for Route 66 stems. This was the era when the motor-going public decided to go out and explore the country in droves, spawning a dramatic increase in roadside commerce.

The development of gas stations, motels and diners mushroomed in the 1950s and 60s and with them creative landmarks to draw tourists in, from twin arrows in the middle of the stretch between Flagstaff and Winslow, Arizona, to motel rooms that resembled Indian teepees at the Wigwam Motel in Holbrook, Arizona — one of the inspirations for the Cozy Cone in “Cars.”

Driving Route 66 was literally an adventure, and Los Angeles resident Jack D. Rittenhouse wrote the adventure guide in 1946, titled “A Guide Book to Highway 66.” It became a bible to travelers of the open road. In it, Rittenhouse provided some important advice, including:

Be sure to have your auto jack. A short piece of wide, flat board on which to rest the jack in sandy soil is a sweat preventer . . . Carry a container of drinking water, which becomes a vital necessity as you enter the deserts . . . An auto altimeter and auto compass add to the fun of driving, although they are not essential.

The same year Rittenhouse’s guide hit shelves, Americans also heard Bobby Troup’s ode to the highway song, “Get Your Kicks on Route 66,” which has been covered by numerous musical groups since.

Wallis’s book captures well the glory years and nostalgia along the famed highway, taking readers on a journey along the road’s entire span just over five years after the last section of interstate bypassed the route for good.

Wallis writes of its heyday with great affection, chronicling the fun and excitement of the journey.

“Route 66 put Americans in touch with other Americans through its necklace of neon lights, Burma Shave signs, curio shops, motor courts, garages, and diners and cafes,” he wrote.

In his volume, Wallis gives high praise to the people along the route who cared for motorists on their journey, especially the waitresses, who he said, “served up burgers, plate lunches, and homemade pie . . . with coffeepots welded to their fists . . . who called everybody ‘honey,’ winked at the kids, and yelled at the cook.”

Wallis also detailed the perhaps less-than-savory, but still memorable aspects of traveling its lengths.

“Route 66 was also a highway of flat tires and overheated radiators; motor courts and cars with no air-conditioning; tourist traps with few amenities; treacherous curves, narrow lanes, speed traps, and detour signs,” Wallis wrote.

According to Tom Snyder, founder of the California Route 66 Association, Route 66 was for travelers, not tourists. To Snyder, tourists are all about rushing to the next popular place and finding the right souvenirs, but travelers are not in a hurry, want to explore, and want to find the souvenir makers, not just the souvenirs.

In 1956, however, just as Route 66 was experiencing its heyday, the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower enacted the Federal Highway Act of 1956, which would authorize the construction of a 41,000-mile network of interstate highways across the country and eventually signal the death knell of the “Mother Road,” which it replaced with five interstates.

Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, formerly vibrant towns in Arizona such as Seligman, Peach Springs and Hackberry were bypassed by Interstate 40 and in a way taken off the map and out of the motoring public’s consciousness.

One of the museum’s plaques explained the result of this very eloquently:

Rest stops were no longer dictated by the unique and enticing attractions along the road, but by large signs that said so. Today, food, gas and lodging facilities are nearly identical from state to state, and the blandness of driving an unremarkable stretch of highway takes its toll.

In a flashback utilizing James Taylor’s “Our Town” as its soundtrack, the movie “Cars” depicts just such a scenario, when a freeway sprang up and bypassed Radiator Springs, causing the cars driving near the town to not even notice it.

The Association

Like many towns along Route 66, Seligman in Arizona depended on the traffic along the highway to sustain its businesses. In 1978, when Interstate 40 replaced Route 66 and rerouted traffic two miles south of town and away from its downtown, businesses suffered, some closed and buildings were abandoned. One Seligman resident, however, refused to take the defeat.

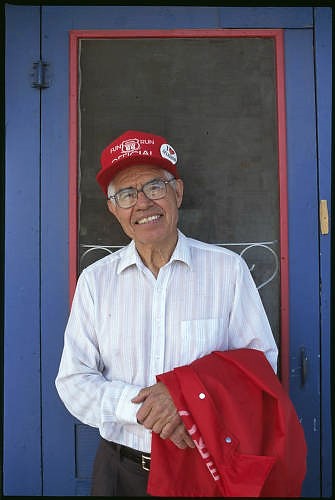

Angel Delgadillo was born in Seligman along Route 66 in 1927, before it was even officially christened with that name in Arizona. He was just a youngster when his family hit on tough times and were about to join what he called “The Grapes of Wrath” people, Wallis wrote in his book. As his family had boarded up their house, built a trailer to haul their things and readied their Model T to leave, Delgadillo’s older brothers got jobs playing music along the route, and they decided to stay.

Delgadillo saw the convoys coming through during World War II and that after the war, the tourists started coming — and kept coming. Even after he grew up, Delgadillo decided to stay at home in Seligman, his only time away at barber college in California. When he finished his vocational training in 1950, he returned and set up his business in his father’s old barber shop and he’s been there ever since, becoming one of Route 66’s greatest advocates.

In February 1987, Delgadillo organized an effort to form the Historic Route 66 Association of Arizona, the first one of its kind. His building became the organization’s first headquarters.

Interest in the cause and nostalgia for Route 66 grew. People started to want Route 66 merchandise so Delgadillo and his wife, Vilma, answered the call, selling memorabilia out of his pool hall to support the Association. In the process, it became the first Route 66 gift shop. Today it’s morphed into “Angel and Vilma’s Original Route 66 Gift Shop.”

In November 1987, the state of Arizona designated old U.S. 66 from Seligman to Kingman as “Historic Route 66,” which later included Kingman to the California border, preserving the longest uninterrupted stretch of Route 66 in the nation. The span has also been declared a National Scenic Byway and has attained All-American Road status. The Association’s inception in Seligman earned the town the nickname “Birthplace of Historic Route 66,” which it proudly displays on its welcome signs.

The association renewed interest in the old road and motorists started driving it again. In 1988, the Association started its annual “Fun Run,” in which cars drive the longest stretch of the famed highway on the first weekend of May. The renewed interest helped give the road new life, and the Arizona Association’s success led to the formation of similar organizations in other states.

The Fun Run, basically a moving classic car show, is still going strong with an average of 800 participating cars every year, even though the weather the first weekend of May can be hit or miss (one year saw snow and another year saw triple digit temperatures), Association Director Nikki Seegers said. It attracts participants from all over the country and world. For instance, one year, a couple drove all the way from Argentina in a Volkswagen Bus.

Driving the stretch from Kingman to Seligman would normally only take an hour and 15 minutes, but during the fun run it takes hours because participants stop at many places along the way. It’s kind of a choose-your-own-adventure event, Seegers said.

At 91 years old, Delgadillo is still the association’s president and still cuts hair in his shop, Seegers said.

The “Cars” Connections

Needing a break from his busy production schedule, in 2001, Pixar’s John Lasseter decided to load his family up in a motorhome and take to the road to get away. On his trip, he found the inspiration for “Cars,” part of which was Lasseter’s own realization from the trip – the importance of slowing down from the frenetic pace he’d been keeping.

The movie would help put Route 66 back into the national consciousness. Wallis became a guide for his team as they traveled the route for research for the movie. Much of the history in “Cars” comes from the mind of Delgadillo himself. Some places along the northwestern Arizona stretch provided direct inspiration for actual places created in the movie.

Seligman: Some say the character of the town of Radiator Springs resembles what visitors will find in Seligman.

Peach Springs: A map of Radiator Springs’ location shown in the movie directly correlates to Peach Springs’ location on the map of the route.

Hackberry: This general store has experienced quite a resurgence over the last few decades and was the inspiration for Lizzie’s Radiator Springs Curio Shop in the movie. Lizzie’s shop’s sign, which reads: “Here it is,” is a direct correlation to the sign of a shop in Joseph City, Arizona, along the eastern part of Arizona’s portion of Route 66.

Sitgreaves Pass: The road and landscape seen as McQueen and girlfriend Sally go on their first date on the highway in the mountain range above Radiator Springs correlates to the hairpin turns (and a little bit the scenery) along this stretch of highway near Oatman, Arizona.

Oatman: It might be a bit of a stretch, but some say the tractors with which McQueen and Mater have a little fun were inspired by Oatman’s wild burros, descendants of the burros from the town’s mining years, which roam the town freely in search of handouts from tourists.

In addition to these landmarks associated with “Cars,” there are plenty of other blasts from the past to explore as one retraces the path of the most celebrated stretch of road in U.S. history.

Visiting Kingman’s Route 66 Museum

The old Powerhouse building became a visitor center in 1997, and the association started the museum on the second floor of the building in 2001, fittingly using money earned from the raffle of a 1964 Corvette Stingray donated to the organization. At first, the association operated the museum, but then the Mohave County Historical Society, which also runs the Mohave Museum and Bonelli House, took it over.

Seegers said there are three types of visitors that come to the museum: those who traveled Route 66 as youngsters and want to relive it, those who love the movie “Cars” and want to see what inspired it and foreign visitors who enjoy the nostalgia of one of the golden eras in U.S. transportation history.

Many visitors who come through the museum have already been experiencing Route 66 and the museum helps them connect to it, Seegers said.

The museum features exhibits portraying three epochs of history along the route: the pioneer era, the Dust Bowl era and, of course, Route 66’s golden age as America’s Main Street with vehicles of each time period as each display’s centerpiece.

While the museum does not feature anything related to the Pixar movie, it definitely provides hints as to the inspiration for parts of the film’s plot.

The museum gives younger visitors the chance to complete a scavenger hunt, looking for specific items on a list within the exhibits, and if they find all the items, museum staff rewards them with a souvenir coin.

In addition to the Arizona Route 66 Museum, the Powerhouse Building is home to a visitor center and gift shop as well as an electric car museum. Admission to the museum also allows visitors to visit the Mojave Museum of History and Arts just a block away and the Bonelli House, the restored home of a Kingman pioneer.

For information on all three museums, visit the Mohave County Historical Society website.

Photo gallery follows below.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

This picture of a historic photo on display at the Arizona Route 66 Museum in Kingman shows Okies in their jalopies forming a caravan down Route 66 in the 1930s, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This historic photo shows and aerial view of Seligman, Arizona, circa 1940 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

This picture of a historic image on display at the Arizona Route 66 Museum shows how Route 66 looked in its "golden years," Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

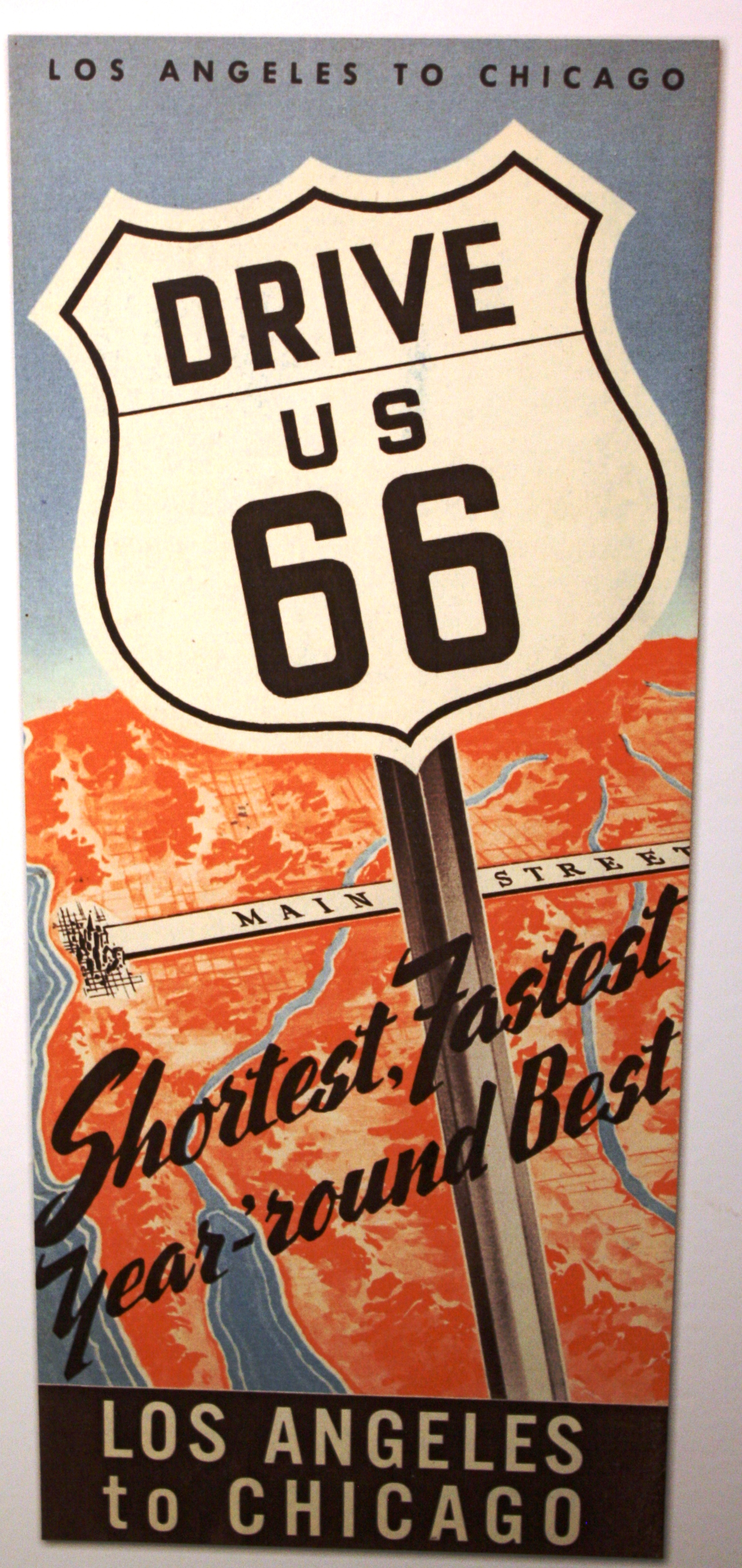

This picture of a museum display shows the cover of a brochure about Route 66 during its heyday, Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Portrait of Angel Delgadillo, the mastermind behind Arizona's Route 66 Association, Seligman, Arizona, 2000 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

Angel and Vilma's Route 66 Gift Shop, Seligman, Arizona, May 2006 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

Seligman, Arizona looking east along Route 66, May 2006 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

Participants of the 2006 Fun Run stop in Peach Springs, Arizona, May 2006 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

Fun Run participants stop at Cool Springs Cabins on the stretch of Route 66 between Seligman and Kingman, Arizona, May 2006 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

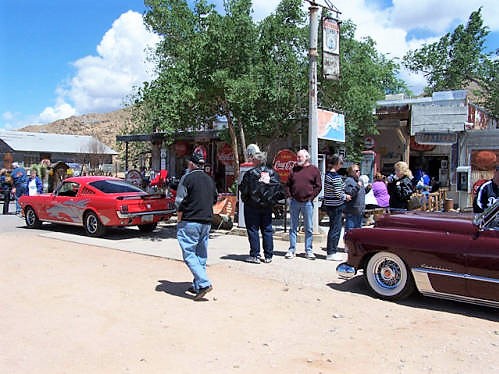

Fun Run participants stop at the Hackberry General Store in Hackberry, Arizona, May 2007 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

A 1958 Impala resembling a character from the movie cars in a parking lot near the Powerhouse Visitor Center in Kingman, Arizona, May 2007 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

Fun Run participants take in the sharp curves of Sitgreaves Pass along Route 66 near Oatman, Arizona, May 2007 | Photo courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Special Collections, St. George News

One of the Arizona Route 66 emblem signs in the parking lot of the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A small Route 66 emblem sign, one of the top sellers among memorabilia merchandise sold by the Route 66 Association of Arizona, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Nikki Seegers, St. George News

A Route 66 map, one of the top sellers among memorabilia merchandise sold by the Route 66 Association of Arizona, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Nikki Seegers, St. George News

The exterior of the Powerhouse Visitor Center, home of the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The north side of the Powerhouse Visitor Center, home of the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The entrance of the Powerhouse Visitor Center, home of the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The view down to the visitor center and gift shop from the museum at the Powerhouse Visitor Center, home of the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Display case of Arizona Route 66 memorabilia at the Powerhouse Visitor Center, home of the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A Prairie Schooner wagon, the centerpiece of the Arizona Route 66 Museum's exhibit on the route's trailblazers of the 19th century at the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

An Okie jalopy, the centerpiece of the museum's Dust Bowl era exhibit at the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The 1950 Studebaker on display as part of the centerpiece of the exhibit on Route 66's golden age, Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Mural depicting the heyday of Route 66 through Arizona in the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Mural depicting the heyday of Route 66 through Arizona in the Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman, Arizona, Nov. 21, 2018 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews