FEATURE – Some might argue that the pioneers who settled “Utah’s Dixie” experienced more challenges than other settlers throughout the state. The hardy pioneers who settled the area had true staying power, having to pit themselves against the region’s numerous challenges, foremost among them its hot, arid climate. They did it without air conditioning and other modern conveniences.

They experienced major struggles in taming the land, especially when it came to water, having to harness a water source to irrigate which was often fraught with its own set of problems. Regularly, these settlers felt they were cursed with either too much water, as floods were a constant challenge and destructive force, or too little water, as droughts made eking out a living a tough proposition.

Two museums in Washington County do a wonderful job of preserving the history of these determined individuals who succeeded, as the saying goes, in making the desert blossom as a rose. They were both built in the same time period – the late 1930s – but for different reasons. One was conceived as a museum from the start. The other served as a library before becoming a museum.

Both represent determination and foresight from groups of people who realized that if they did not preserve important reminders of history, they might fall by the wayside and be destroyed and forgotten.

Daughters of Utah Pioneers (McQuarrie Memorial) Museum

Since the inception of the Washington County unit of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers in 1921, the organization collected artifacts of early pioneer history as well as biological sketches of prominent early settlers written by their descendants. It also sought an edifice where it could house that collection but kept hitting numerous roadblocks.

“Time and time again, a drive was launched to obtain one of the historic buildings of our community for a relic hall, but each time we were unsuccessful, for we found that buildings cost more money than we were able to raise,” wrote Hazel B. Bradshaw, president of the Washington County DUP in the 1930s, in a sketch of the museum building.

The organization felt some urgency to preserve these important reminders of the past, as Bradshaw explained so well:

“Each year we heard of priceless relics being destroyed because their owner did not appreciate their value, and one by one our old public landmarks were being razed for, or turned into gas stations, factories, and wineries, etc., and their contents destroyed.”

In 1936, Josephine Brooks Pace, DUP “Custodian of Relics,” was given the task of securing a place to display the DUP’s collection of pioneer artifacts. She wrote dozens of letters to potential benefactors, but met only resistance. Fortunately, Pace decided to write Hortense McQuarrie Odlum, a childhood acquaintance, expressing her concern over the loss of so many of the relics due to lack of storage facilities and lamenting the dire need for a relic hall. Odlum answered the letter immediately, offering her financial support to ensure such a building came to fruition. Odlum donated $17,500 to construct the edifice in honor of her pioneer grandparents, Robert and Mary Gardner and Hector and Agnes McQuarrie. Her grandfathers played an integral role in cutting and hauling the lumber needed in the construction of the St. George Temple. Her grandmothers were connected to early retail operations in the area.

Odlum grew up in St. George and attended Woodward School. She attended Brigham Young University and married Floyd B. Odlum, who became financially successful later on as President of the Atlas Corporation. Mrs. Odlum later became the president of Bonwit Teller department store on New York’s 5th Avenue, which the Atlas Corporation acquired, helping bring it back to profitability after years of financial distress. She was the first female president of a modern department store. In her sketch, Bradshaw called Odlum one of the best dressed and hardest working women in the country.

At first, the building was to be known as the Odlum Memorial, but Odlum herself later chose the name McQuarrie Memorial Museum. Walter Cooke Jago of New York City served as the architect and David Woodbury and Evan Cottam, both sons of Washington County pioneers, were the contractors. Washington County provided the land to the DUP just north of the county’s pioneer courthouse for the museum’s construction.

Pace headed the building’s ground breaking on January 5, 1938. Robert Worthen laid the cornerstone on February 27 of the same year and placed a time capsule in a metal box, which included a list of all those involved in bringing the building to fruition, as part of the ceremony.

“Pervading the entire services was a sentiment of deep appreciation to Mrs. Odlum . . . whose generous bequest had made the edifice possible, and of Mrs. Josephine B. Pace through whose solicitation the gift was received,” wrote DUP Recording Secretary Clara Whitehead about the event.

Whitehead’s meeting notes from that April explain that President Bradshaw reported that there had been great interest in the building at the state DUP convention of that year and that Bradshaw “expected a large number of visitors at the dedication of the building and asked officers to be ready to give all the time possible to make the dedication of memorial building one of the greatest days of Dixie.”

At the time of its construction, the building measured 45 by 55 feet with walls of red brick held together with white mortar.

“A full cement basement with a ten foot ceiling provides a roomy auditorium,” Bradshaw noted in her sketch. “Besides two large rooms for relics, the main floor contains two smaller ones for (an) office or library as well as a restroom and front entrance hall. Careful attention has been given throughout to make it practically fireproof, and so enduring that it would last for ages.”

June 17, 1938 became the building’s dedication day with a luncheon attended by 216 DUP members and guests complete with music that included “My Dixie Home” by the late Anthony W. Ivins as well as an address by Odlum herself, “assuring the daughters of Dixie that what she had done was not an impulsive gesture but an expression of love for her pioneer ancestors, her old home town and her many friends and it had given her the greatest happiness for her life,¨ Whitehead noted.

The actual dedication ceremony, with a dedicatory prayer offered by St. George Stake President William Bentley, took place that evening followed by a Dixie Junior College and Dixie High School band concert. As part of the ceremony and as a token of their appreciation, the DUP gave Odlum a “Book of Memories” containing pictures and biographical sketches of members of her family as well as tributes from some of her old friends. The organization also gave her a gold key, symbolizing perpetual ownership of the museum building.

“Let us pause for just a moment in retrospection to the memory of those grand old pioneers, who through trials and trouble and untiring energy made all this possible,” Annie R. Pace said in her dedicatory address. “Let’s scan the full story picture since the day the first weary company came down over the Black Ridge. That was the first moving picture in Dixie. There has been none like it since – it can never be reproduced.”

An open house followed the day after the dedication to show off the building.

In addition to a museum, the building originally served as a community center with the DUP renting it out for various events to earn some money. It even served as a “nursery school” for the school district for a short time.

From the beginning the DUP has been strict about access to the items in the museum.

“It was decided that no relics would be let out of the building for anything or anyone, and that the relic committee was to have charge of relics, keep them in place and well arranged,” Whitehead wrote in her meeting notes on March 29, 1940.

Even today, museum patrons cannot take pictures of the items on display, which include clothing, dishes, furniture, pottery, quilts and other items from the pioneer era. The museum continues to receive pioneer artifacts, photos and histories. It digitizes photos and histories and can provide copies of them to requesting patrons who are direct descendants of the pioneers for whom it has the information.

The museum building is not in its original 1938 state as a 2,000 square foot addition was added in 1985 which also provided handicap access.

Hurricane Pioneer Museum

Many Hurricane old timers have fond memories of the old white chapel that stood at the southwest corner of state and main streets. Built in 1940 as the Zion Park Stake Center and Hurricane North Ward chapel, it had a relatively short life span. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints decided to demolish the chapel, which had developed structural problems, and realized bringing it up to code was not economical. It was razed in 1985. That same year, a new building for the Hurricane branch of the Washington County library was completed, leaving vacant the old sandstone library built between 1938 and 1940.

In August 1986, Hurricane Mayor Dewey Hardcastle called a meeting to discuss options for saving and utilizing the old library. Twenty-five people attended that first meeting and decided the building should become a pioneer museum. Twelve people attended the second meeting and they organized a governing committee, electing Verdell Hinton, who had been personally invited to the meetings by the mayor, as chairman of that committee.

Hinton was a great fit for the job. His parents, Vernon and Isabell Hinton, were one of the first 11 families to settle Hurricane. After a career teaching 6th grade in both Las Vegas, Nevada and Fair Oaks, California, he had just retired in his hometown and looked forward to a retirement that consisted of devoting himself to woodworking, “building knick knacks and birdhouses,” he said.

That retirement dream was not meant to be as he fully devoted his energies to preserving Hurricane’s history in the soon-to-be museum and heritage park.

The first hurdle he and his committee had to overcome was to acquire the adjacent corner lot where the white chapel and Relief Society building once stood to serve as the heritage park and parking lot. Hinton said they wanted to avoid something like a fast food chain going in and make sure the lot was preserved for civic use as it was “kind of a sacred place” since church buildings had been on it.

The committee hoped to convince the church to donate the property and sent Hinton and Robert Langston to Church headquarters to make their case, equipped with a drawing of their vision for the land, a heritage park and parking lot.

“Perhaps it was a slow news day, or some television station executive had unusual vision but for whatever reason that remains a mystery, a TV news crew awaited Bob and Verdell when they emerged from the meeting prepared to give at least brief fame to them and their cause,” Victor Hall wrote in a booklet entitled “Hurricane Museums and Other Historical Memorials” available at the museum. “Buoyed by the positive reception at Church headquarters, the committee plunged into the thousand tasks that needed to be addressed, raising money being the most urgent.”

The first step was forming a non-profit organization that could grant tax-free status to potential donors, which led to the formation of the Hurricane Valley Heritage Park and Museum Foundation. To start the funding drive, Hinton was able to track down the names and addresses of nearly every Hurricane High School graduate since 1928 and sent them a letter describing the project and inviting donations.

Hinton was blown away by the response.

“Over the several months, it was like Christmas,” Hinton said.

With some of that money, the committee erected a sign on the lot, which was just full of weeds at the time, explaining what it was going to be and inviting further donations. Overall, this fundraising campaign was “very successful,” Hinton said.

The church’s initial response to the invitation to donate the lot was not what the foundation members wanted to hear. The church said they could have the lot, but they would have to pay the $150,000 razing cost or provide another piece of property in return, both Hall and Hinton explained. That was money and resources the foundation did not have.

Hinton and Langston refused to give up, however, knowing their cause was worthy. They started to try alternative approaches. A regional representative advised them to go through usual priesthood channels which led Hurricane Stake President Dennis Beatty to get involved with a new proposal, which led to an agreement in April 1987 that called for the church giving the foundation a renewable lease on the property for $1 a year.

The plan for the heritage park called for a pioneer statue and monument as a centerpiece in the middle, a sandstone fence around the perimeter of the park, a waterfall, a small pool and bridge, commemorative plaques detailing important aspects of local history placed at strategic points and concrete pads laid where machinery or vehicles could be displayed.

Foundation members decided on a sculpture of a young pioneer family giving thanks for their new home and opportunities as the centerpiece of the park and, unable to hire a professional sculptor due to lack of funds, found amateur sculptor George Cornish, who had recently retired in Hurricane, to create the sculpture. Cornish admitted that he had never attempted anything on that scale before but felt confident he could do it, needing only a warm place to work and some clay, Hall wrote. The school district provided a corner in the Hurricane High School shop building as Cornish’s workplace.

“George was there that winter sculpting away during almost every hour that the building was open and by spring the depiction of the husband, wife and son expressing gratitude to the Lord was completed,” Hall wrote. “Although George donated his time, the bronze-casting company in Orem needed $40,000 to cast the final statue.”

After looking at what Cornish had sculpted, the committee asked him to make some modifications and even considered another option at the last minute, having reservations about the quality of Cornish’s work. Some time later, a Utah State Arts Council expert appraised it and noticed it has some technical flaws, but that it captured “the sweat, the calluses and the spirit of the pioneer settlers” far better than a photo-perfect statue would,” Hall wrote.

The Bureau of Land Management gave permission to quarry sandstone from a source near Cedar Ridge about five miles south of Cane Beds, Arizona. Horace Cornelius and his brother, Kenneth, from Virgin, were instrumental in providing labor and equipment necessary to obtain the necessary rock and Horace, a master rock mason, went on to design the central monument upon which the statue stands, Hall explained.

Numerous local residents and organizations, as well as Hurricane natives who had moved away, contributed their time and resources to the effort in developing the park. For example, Dell Stout laid the concrete pads where the donated historic machinery and vehicles now stand and Milo Finch, a local landscape architect, volunteered to create the ponds and waterfall, which have since been removed. One former resident who contributed greatly was Delmar Hinton, who became a successful California nurseryman and donated trees and shrubs to the park. Even an LDS stake in Springville, Utah, contributed to the effort by helping with painting, washing windows and other chores as part of a service project while attending a youth conference based in Zion National Park.

“It seemed like one after another people were volunteering,” Verdell Hinton said. “It impressed me how willing people were to help out.”

Hinton explained that it got to the point that they did not have to fundraise as much because of the amount of donations of materials and labor they were receiving.

A dedication ceremony took place in the fall of 1989. The program thanked those who donated their time and money towards the project and reminded everyone of the pioneer heritage they were preserving. The high school band provided the music and Lynn Sanders cooked up a Dutch oven dinner for the occasion. Hinton said demonstrations of old pioneer skills such as rope-making and cow milking were also part of the ceremony. Hurricane Stake Patriarch Grant Langston offered the dedicatory prayer and the grand finale consisted of Cornish unveiling his statue.

The museum is not just the old library and its surrounding Heritage Park. It also includes the Ira and Marian Bradshaw home kitty corner across the street. The Bradshaws were one of Hurricane’s founding families. Ira Bradshaw was the first president of the Hurricane Canal Company. The home hosted Hurricane’s first church services and even served as the first school.

In the 1930s, soon after the Bradshaws died, Washington County purchased the home and turned it into a senior center. About 1960, when a larger facility was acquired, it started renting the house out. The County Commissioners eventually decided to raze the home and invited local residents to retrieve whatever they could see of value, Hall wrote.

“They set to with gusto and a near skeleton soon resulted,” Hall explained.

Being made aware of the home’s historical significance, Hinton and others approached the County Commission about deeding the property to Hurricane City for restoration. Unimpressed at first, the commissioners acquiesced and Hinton, Robert Langston and Jane Whalen became driving forces in its restoration, which went similarly to the work on the museum and Heritage Park with many local residents and organizations happy to donate time and resources for its restoration. The backyard of the home became a place to display other relics of Hurricane’s past, including a blacksmith shop, a one-room cabin and other outbuildings as well as antique farm implements.

Hinton was involved with the museum and heritage park foundation until 2003. He said current Museum Director Phyllis Lawton has done a “marvelous job” of keeping it going. For the most part, funding from Hurricane City and federal grants have kept the museum running, he said.

When asked if he wishes his retirement had gone as he originally hoped, Hinton was quick to say that he does not regret how it went one bit.

“I haven’t felt sad for a moment,” he said. “It’s 100 percent better than what I thought I’d be doing in my retirement years. I’ve left something people can remember and enjoy.”

He said he is glad that he had a hand in preserving history he feels would be gone otherwise.

Visiting the museums

Current McQuarrie Memorial Museum Director Teresa Orton said the museum is doing well today with a recent influx of visitors, even tourists from all over the United States and other countries. The DUP also recently upgraded and cleaned the building.

“Our grand old 80-year old lady needed a facelift,” Orton said. “We power washed, painted and stuccoed the outside so she looks fresh and clean. At night with the new security lights she absolutely glows.”

Recently, the museum has been receiving new donations and is planning new displays to show these items and tell their stories, Orton noted.

“We are not a dusty old pioneer museum with artifacts put on a shelf and forgotten,” Orton said. “We are trying to make the pioneer history and lives more vibrant and relevant to the current society. When people come to visit (or re-visit) they are pleasantly surprised at how our photos and artifacts are displayed and the knowledge of our docents.”

As a new way to engage the public, the museum is going to put QR codes on some items to be able to tell more about the history of it, which the museum hopes the younger museum patrons will enjoy, Orton said.

The museum truly has something for all ages as they have a scavenger hunt and trivia games geared towards children. The museum also offers ways to customize group tours to fit their interests, such as searching for a particular pioneer name, Orton explained.

The Hurricane Pioneer Museum is also full of family histories and photos, both on display and in binders available for patrons to peruse. Museum Director Phyllis Lawton said the museum continually switches up displays to keep things fresh.

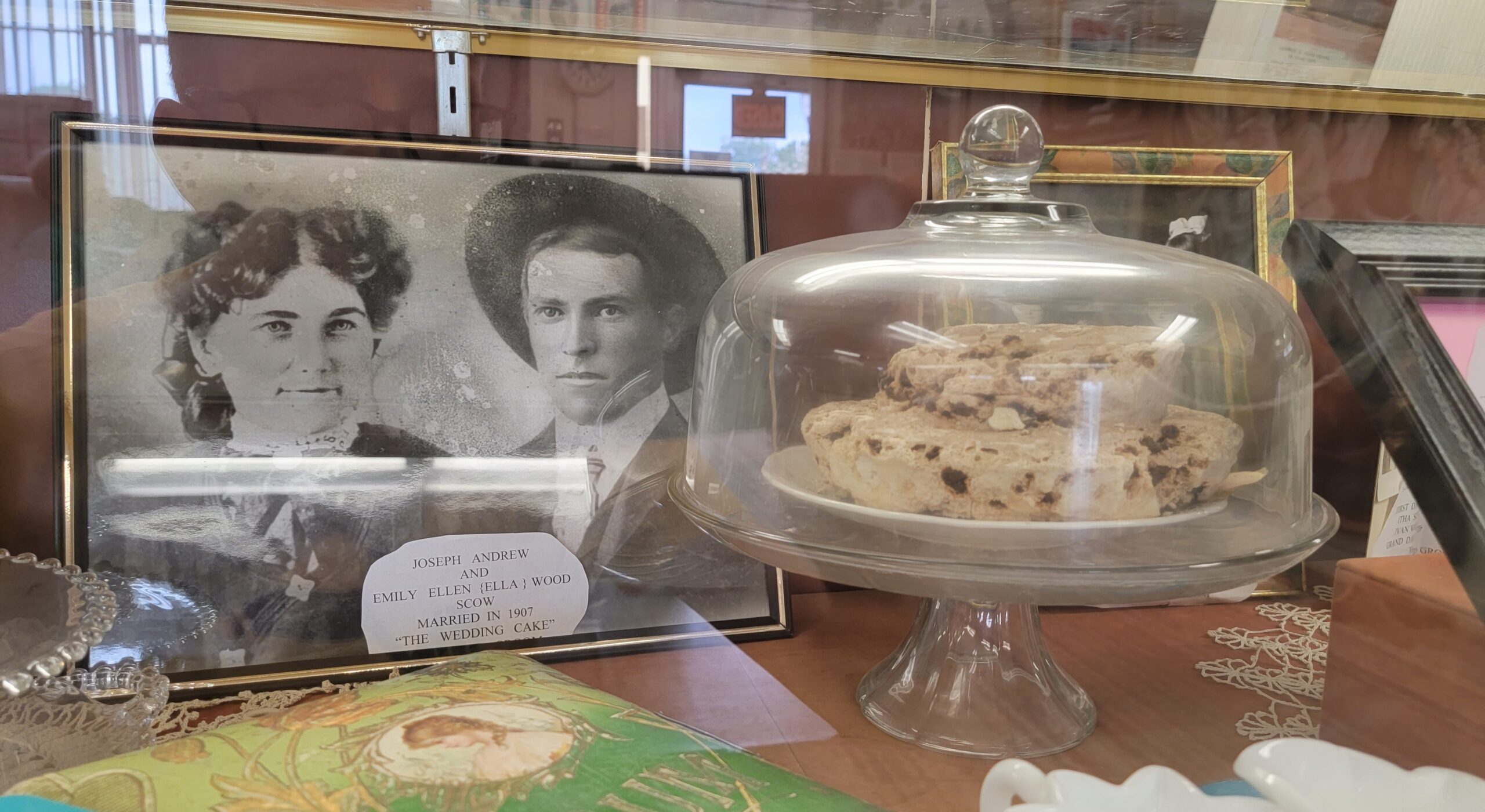

Two of the Hurricane museum’s most unique artifacts are food items: a fruitcake baked in 1907 and bacon cured around 1945. In fact, for a time, the museum displayed a sign above its front door that read: ¨We have the cake,¨ Lawton noted.

Both museums sell a plethora of books about local history for those who want to find out more. The DUP Museum also has regular programs and presentations. To find out more about the museum and its programs, visit its website.

These two museums are not the only museums worth visiting in the county to learn more about local history. Others include the Silver Reef Museum and the Washington City Museum. Additionally, the old Pioneer Courthouse next to the McQuarrie Memorial Museum contains interesting displays about local history and holds programming of its own. The Brigham Young Winter Home and Jacob Hamblin Home, operated by the LDS Church with senior missionaries as guides, also provide unique glimpses into the pioneer history of Utah’s Dixie.

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

This historic photo shows St. George DUP members posing at the groundbreaking of the McQuarrie Memorial Museum groundbreaking, St. George, Utah, Jan. 5, 1938 | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

This historic photo shows Hortense McQuarrie Odlum, whose financial gift funded the museum building, and Josephine Pace, DUP Custodian of Relics, chatting the day of the dedication ceremony, St. George, Utah, June 17, 1938 | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

This historic photo shows DUP and St. George dignitaries posing in front of the museum on the day of its dedication, St. George, Utah, June 17, 1938 | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

This historic photo shows the dedication ceremony of the McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George, Utah, June 17, 1938 | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

This historic photo shows the McQuarrie Memorial Museum exterior as it looked in the late 1970s, St. George, Utah, May 13, 1978 | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

This historic photo shows the back of the museum after the 1985 addition, St. George, Utah, 1985 | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

Today, the museum has a large sign outside to tell the public what it is, St. George, Utah, April 20, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The exterior of the museum today does not look much different than it did when it was built in 1938, St. George, Utah, April 20, 2017 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Docents greet visitors in the museum lobby to orient them about the museum collections, St. George, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

The McQuarrie Memorial Museum displays a bed and wardrobe used by 2nd LDS Church president Brigham Young, St. George, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

The museum includes a display of military uniforms, including one from the Nauvoo Legion, St. George, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

Pioneer quilts are part of the McQuarrie Memorial Museum displays, St. George, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

The McQuarrie Memorial Museum features a basement with ample seating for its regular presentations about local history, St. George, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of McQuarrie Memorial Museum, St. George News

This historic photo shows the old white chapel which was on the lot now occupied by the Hurricane Valley Heritage Park, Hurricane, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News

Sons of Utah Pioneers officers pose at the base centerpiece statue of the Hurricane Valley Heritage Park, Hurricane, Utah, circa 1989 | Photo courtesy of Hurricane Pioneer Museum, St. George News

Verdell Hinton, who was integral in getting the Hurricane Valley Heritage Park and Pioneer Museum going, stands by the centerpiece statue of the Heritage Park soon after its dedication, circa 1989 | Photo courtesy of Hurricane Pioneer Museum, St. George News

Current Hurricane Pioneer Museum Director Phyllis Lawton poses with her mother, Verna Hinton, in front of the John Nock and Emma Hinton descendant display in the Hurricane Pioneer Museum, Hurricane, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Hurricane Pioneer Museum, St. George News

The Hurricane Pioneer Museum is housed in the old sandstone Hurricane Library building on the southwest corner of State Street and Main Street in Hurricane, Utah, June 7, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A heritage park honoring early Hurricane pioneers sits adjacent to the Hurricane Pioneer Museum, Hurricane, Utah, July 7, 2011 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A statue of a pioneer family giving thanks sculpted by George Cornish is the centerpiece of the Hurricane Valley Heritage Park, Hurricane, Utah, June 7, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Hurricane Canal display in the Hurricane Pioneer Museum tells the story of the birth of Hurricane, Utah, June 7, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The 1907 wedding cake of Joseph and Emily Wood is one of the most unique artifacts on display at the Hurricane Pioneer Museum, Hurricane, Utah, June 7, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Bacon cured around 1945 is another unique artifact on display at the Hurricane Pioneer Museum, Hurricane, Utah, June 7, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

A room in the Hurricane Pioneer Museum displays what an pioneer kitchen might have looked like with period implements, Hurricane, Utah, June 7, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Another room in the Hurricane Pioneer Museum displays the descendants of John Nock and Emma Hinton, one of the founding families of Hurricane, Utah, June 7, 2021 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The Bradshaw Home is an extension of the Hurricane Pioneer Museum across the street, Hurricane, Utah, July 7, 2011 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page, follow his Instagram account or subscribe to his YouTube channel.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2021, all rights reserved.